How one accountant links Whitaker's nonprofit to network of dark money groups

The offices of the Foundation for Accountability and Civic Trust (FACT), the nonprofit once headed by acting Attorney General Matthew Whitaker, are located at a shared workspace on K Street in Washington, D.C., a couple blocks from the White House. FACT has used the address since 2014 on each of its publicly available tax returns. Yet, in all those years, the organization never reported hiring any employees to work there, and its current executive director works at a law firm in Des Moines, Iowa.

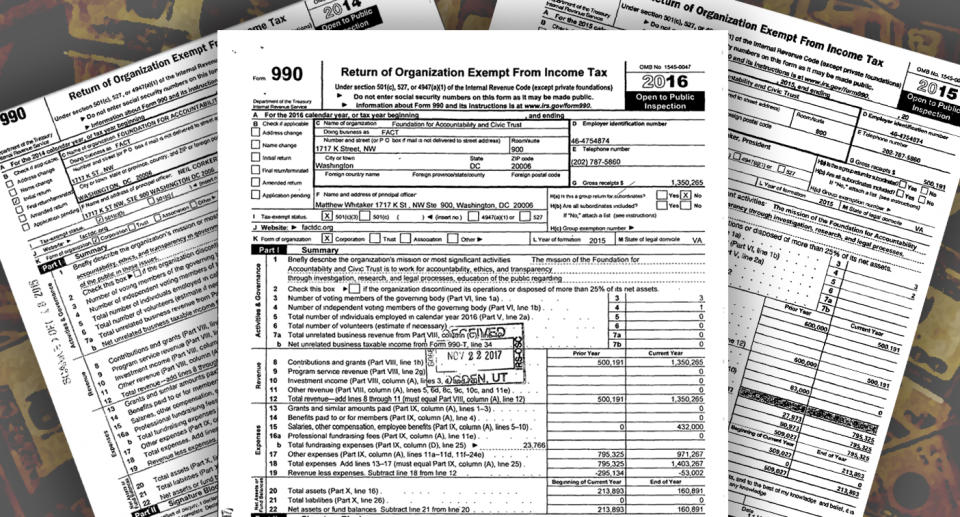

Who funds FACT is unclear, because it relies on “dark money,” funding from anonymous donors who pursue political agendas. What little information is available about FACT’s finances can be gleaned from its publicly released 990 tax filings, which show that the nonprofit paid Whitaker more than a million dollars over his three-year tenure there. FACT’s funding is collected by another nonprofit, Donors Trust, and then sent on anonymously.

In recent weeks, FACT, which public records show has connections to a number of other conservative groups through the same family of activists, has drawn renewed attention to the role of dark money. Yet one important link among these nonprofits has largely escaped notice — the accountant who prepared the nonprofit’s tax returns.

Thomas Raymond Conlon, the Maryland accountant responsible for the tax returns filed by Whitaker’s former nonprofit, is also linked to other prominent conservative organizations funded by dark money and whose only public face as an organization is often a UPS box or virtual office in the Washington, D.C., area. Conlon, whose own accounting business has been penalized for failing to file tax returns, has created a paper trail with notable errors in his work for some of those groups, according to public records reviewed by Yahoo News.

While the IRS does not appear to have taken action against any of Conlon’s clients, an examination of his role as their accountant provides a window into an expansive network of dark money groups and how they operate.

Marcus Owens, former head of the exempt organization division of the IRS, told Yahoo News in an interview that he found it “odd” for the organizations, many of which have substantial resources, to turn to an accountant like Conlon, who appears to work alone and have issues with filings for his own business. “And maybe there’s a reason, and a valid reason, but it’s certainly a curiosity that Whitaker and FACT are fellow travelers with lots of unusual things.”

Among Conlon’s clients is FACT, a tax-exempt charity that promotes itself as a conservative ethics watchdog and was headed by Whitaker until he joined the Justice Department. Earlier this month, President Trump forced then Attorney General Jeff Sessions to resign, elevating Whitaker to head the department.

Now, Whitaker’s prior work at FACT, which paid him $1.2 million over three years, is drawing public attention. Among other concerns, critics say FACT appears to have engaged in political activities, despite its status as a tax-exempt charity, whose donors are permitted to deduct their donations to FACT from their income taxes, and rules that prohibit it from getting involved in campaigns or supporting candidates.

In the past, concerns have been raised about other dark money-funded nonprofits organized under section 501(c)(4) of the tax code; the IRS has permitted those so-called social welfare organizations to intervene in political races as long as that is not their primary activity (and as long as they disclose their political activities, pay appropriate taxes and otherwise follow the law). Practically speaking, this has meant a 501(c)(4) can spend up to half its money on political activities.

FACT’s status as a tax-exempt charity under Section 501(c)(3) of the tax code leads to heightened concerns, because those organizations are subject to stricter rules that prohibit any interventions in political races, monetary or otherwise.

But even in the opaque world of dark money, Conlon’s role as an accountant stands out. A review of public records reveals that Conlon, who filed tax returns for FACT, has also performed tax accounting services for a dizzying array of connected nonprofit organizations, both 501(c)(3)’s and 501(c)(4)’s. Some of those filings contain errors, which could open the door to scrutiny of those organizations.

It’s happened before. Another high-profile conservative nonprofit client of Conlon’s, the American Conservative Union (ACU), underwent a lengthy investigation and paid a hefty fine to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) over a transaction that came to light when ACU’s tax return, which Conlon had prepared, had to be amended because it had been contradicted by its annual audit, which he also conducted.

Conlon’s other clients include a number of 501(c)(4) organizations, including the Judicial Crisis Network (JCN), a group that has been involved in partisan Supreme Court battles; and the National Organization for Marriage (NOM), which has worked to roll back same-sex marriage; the Annual Fund; and the Catholic Association. Another client, the National Catholic Prayer Breakfast, which holds an annual event the president traditionally attends, is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3).

Additionally, Conlon prepared returns for tax-exempt subsidiaries of JCN and NOM, the Judicial Education Project and National Organization for Marriage Education Fund (NOMEF), each also a 501(c)(3).

Conlon also prepared tax returns for the Wellspring Committee, a pool of anonymous donations that funds JCN and other conservative groups, and ActRight, a complex of nonprofit entities organized for various purposes, including fundraising and going after the IRS for alleged bias against conservative nonprofits.

All of those organizations have been linked at one point in time to conservative activists Ann and Neil Corkery. The married couple have served on the boards of, as officers of, or as the custodians of records for all those entities, according to tax filings; the Corkerys’ daughter Kathleen has served on the board of the Wellspring Committee.

The deeply private Corkerys have roots in Florida, where news stories from the 1990s link Ann and Neil to the conservative Catholic organization Opus Dei. The Corkerys now live in Virginia, where Ann is an attorney, and Neil draws salaries from several of the nonprofits to which he is connected. Calls to several phone numbers and messages to several email addresses associated with the Corkerys and their charities were not returned.

In an interview with Yahoo News, Conlon declined to comment on client matters and his relationships with individuals, including the Corkery family.

A number of dark money-funded groups, like those in the Corkery network, have been able to take advantage of the ambiguity in rules around tax-exempt charities. Section 501(c)(3) prohibits organizations like FACT from participating in political campaigns or supporting candidates running for office. “Violating this prohibition,” the IRS warns, “may result in denial or revocation of tax-exempt status and the imposition of certain excise taxes.”

However, where the election law provides a clear distinction between advocacy for or against a candidate’s election and what’s known as issue advocacy based on the specific words used, the tax code’s rule is both more restrictive and has more gray area, according to Owens, the former IRS official.

“The legal standard under the tax law for what constitutes ‘campaign intervention’ is a much broader concept than it is under federal election law,” Owens said about the rules for 501(c)(3) organizations.

Rather than applying a bright-line rule, the IRS looks to “all the facts and circumstances,” to see if the organization’s activities have a political pattern, Owens said. “In other words, does it do things consistently over a period of time or does it suddenly seem to jump into particular issues or take political actions when it seems that an election is imminent?” he said. “Does it target its messaging to particular geographic areas where there is a close race or something of that nature?”

Under Whitaker’s leadership during the 2016 election season, FACT appears to have tested the boundaries of the prohibition against political activity. On Oct. 24, 2016, two weeks before the elections, FACT filed a series of complaints with the Federal Election Commission signed by Whitaker against 14 Democratic congressional candidates, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

Whitaker also repeatedly used FACT to attack Hillary Clinton on television and in writing, far more than any other candidate, according to an analysis by the Washington Post. (A typical post by Whitaker on the charity’s website, dated March 10, 2016, is titled “FACT Releases Top 10 Most Ethically Challenged Hillary Emails.”)

Rather than hire and train employees to carry out FACT’s mission to “work for accountability, ethics and transparency in government through investigation, research and legal processes,” Whitaker outsourced the investigation and research work. In 2015 and 2016, FACT paid an overtly political Republican opposition research firm $324,150 for “research.” That firm, America Rising, has been called “the unofficial research arm of the Republican Party.” It states on the website for its political action committee that its “sole purpose is to hold Democrats accountable.”

In a statement to Yahoo News, FACT Executive Director, Kendra Arnold stressed that it is “non-partisan” and that the group has “filed several complaints against current and former Republican Members of Congress.”

The Department of Justice did not respond to a call and message seeking comment from Matt Whitaker.

FACT filed congressional ethics complaints and issued statements targeting alleged lapses by Republicans. They have also filed FEC complaints targeting alleged fundraising scams.

“Like nearly all nonprofit organizations — including those with similarly stated missions — FACT does not and is not required to release its internal board deliberations or donor information,” Arnold’s statement said. “This protects free speech rights of all of these groups’ supporters as outlined in the First Amendment.”

However, from a review of the FEC’s records, the organization’s actions appear to have disproportionately focused on Democrats, such as the series of complaints filed in the two weeks before the 2016 election. Whether those FEC complaints against Democrats, considered alone, violate the tax rule against political activities “is a hard case,” according to Philip Hackney, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law who studies nonprofits. However, he said, the use of America Rising for research might make it easier to find a violation.

Hackney gives as an example the watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), a nonprofit that was also filing FEC complaints. “I don’t think anybody would argue that they’re arguing for or against a candidate,” he said. “They have a particular perspective on procedure and they tend to follow that pretty well.”

FACT was intended to be a conservative doppelganger for CREW, which some Republicans perceive as their partisan antagonist, according to a report in New York magazine. CREW, for its part, denies engaging in political activities and says the line for nonprofit charities is clear.

“We do not coordinate or accept tips from campaigns or political groups,” Jordan Libowitz, a CREW spokesman, wrote to Yahoo News. “We do not advocate for or against candidates. We don’t file complaints against officeholders shortly before elections. In short, we stick to our mission and our (c)(3) status — we have no desire to try to influence elections.”

While FACT’s status as a nonpartisan charity does not appear to have been formally challenged to date, NOMEF in 2010 faced formal complaints from gay rights groups that its affiliate the Ruth Institute had crossed the line into prohibited political activities. Among other activities, the gay rights groups complained that a Ruth Institute official had spoken on behalf of the tax-exempt charity at a campaign event for Carly Fiorina, then a U.S. Senate candidate in California.

No public action by the IRS resulted from the gay rights groups’ complaints; the Ruth Institute has since severed its affiliation with NOMEF and become an independent organization.

As the tax accountant for FACT, Conlon would have been responsible for ensuring that FACT’s financial reporting was true, correct and complete, but not advising on its activities. “I just do the 990s,” Conlon said, referring to the IRS form on which tax-exempt organizations file their returns. “I don’t get involved in the politics.”

But Conlon is responsible for the organizations’ taxes, and some of the returns that Conlon prepared for FACT, Whitaker’s nonprofit, contain errors and contradictions that are identifiable by outside observers.

For instance, FACT’s 2014 tax filing says the organization wasn’t formed until 2015 and is registered in Washington, D.C. In fact, the entity was formed in 2012 and registered under another name in Virginia, where it has remained ever since, the records of that commonwealth show. (FACT underwent two name changes in 2014, ultimately settling on its current name in October 2014, the same month Whitaker was hired, according to his financial disclosures.) “Amended returns are filed to correct the situation if there’s an error,” Conlon said.

FACT’s 2015 and 2016 tax filings include the same error about its year of formation but do not repeat the error about where it’s registered. (At the time this article was published, FACT’s 2017 return was not yet available.)

Another error is in FACT’s 2015 tax filing, which says on its first page that the charity spent $0 on “salaries, compensation and other benefits” during the year. However, on its seventh page, the same filing reports that FACT paid Whitaker a $252,000 salary and, on its 10th page, that FACT spent $289,500 overall on compensation in 2015.

After Yahoo News pointed out the discrepancy in FACT’s 2015 filing, Conlon acknowledged that the entry on the first page is erroneous. “It should not have been zero,” he said, adding that the correct compensation numbers appear later in the filing and on an attached schedule. FACT declined to comment on these discrepancies in its tax filings, or other specific questions about its activities.

“They certainly can be ascribed to carelessness, at least those errors,” Owens observed about the discrepancies in FACT’s tax filings. “But it makes you wonder about the appropriateness, the adequacy, the assurance of the answers they do put down in the return. Was it really only $250,000 in compensation, or was there a typo there too? Did they forget to list some of their expenditures? … You start seeing errors and you have to assume that everything is potentially incorrect.”

ProPublica reported another example from 2010: The Annual Fund, a nonprofit then linked to Neil Corkery, had indicated on a Conlon-prepared return that it had not engaged “directly or indirectly” in political activities, despite providing major funding for two nonprofits that had purchased political ads during the 2010 midterm elections.

Conlon also has had tax filing trouble with his own business, including failure to file certain tax returns of his accounting businesses with Maryland, according to the state’s online business records for limited liability companies. It appears from the records that he abandoned one incarnation of his accounting firm after a missed filing eight years ago, forfeiting the right to do business in its name, and recently jeopardized a replacement entity with another missed filing.

The firm Conlon and Associates is presently designated as “not in good standing” because it has not yet filed a personal property return due this year. The designation means, according to a state website, that “the business entity is not in compliance with one or more Maryland laws”; the state’s records give the reason for the designation in Conlon and Associates’ case as “Personal Property: Return Due For 2018.”

Moreover, public records suggest this isn’t the first time that has happened. The currently active Conlon and Associates, formed in April 2016, is the second incarnation of the business, according to Maryland’s records. In October 2011, a previous entity, “Conlon and Associates LLC,” with the same address, was “forfeited for failure to file [a] property return for 2010,” according to the records.

Contrary to the state’s records, only one entity has ever existed, Conlon told Yahoo News. “As far as I know,” he said, “I only have one LLC and have only had one LLC all along.” Conlon said he was not previously aware of the tax issues for the currently active entity and plans to resolve them promptly.

When a Maryland entity is forfeited, “the right of the entity to conduct business in the State of Maryland has been relinquished and it has no right to use its name,” according to the state.

Conlon signed some of the tax filings he prepared for FACT and the other conservative groups between 2011 and 2015 using the defunct firm’s name, and before Maryland’s records indicate that the replacement firm was formed.

Public records also show that a personal tax lien of more than $6,000 was filed against Conlon in 2009 for unpaid state taxes in the years from 2005 to 2007; the lien was paid and satisfied a year and a half later.

Easily identifiable errors notwithstanding, none of the nonprofits Conlon has prepared returns for appear to have been reprimanded by the IRS, which experts agreed was not surprising.

“The threat of enforcement has kind of completely gone away after the (c)(4) scandal,” said Brian Mittendorf, the accounting expert, referring to the 2013 controversy over the IRS allegedly searching keywords associated with conservative nonprofit groups in order to target those nonprofits for added scrutiny. The scandal caused a furor in Congress and led President Obama to demand the resignation of the IRS’s commissioner.

A Treasury Department inspector general’s report issued later, after Obama had left office, found that the IRS had searched keywords associated with both liberal and conservative groups. Nonetheless, the Trump administration chose to settle two lawsuits brought by conservative groups over the scandal, one of them reportedly for a seven-figure sum.

One of Conlon’s conservative clients has faced repercussions, however — not from the IRS, but from the Federal Election Commission.

In 2012, Conlon prepared the tax filings of, and served as the auditor for, ACU, the nonprofit best known for organizing CPAC, an annual gathering of conservatives.

In ACU’s tax filing for 2012, the organization indicated to the IRS that it had not engaged in any political activity. This was contradicted by the “independent auditor letter” that Conlon wrote a few months later, which showed in its attached tables that ACU had spent $1,710,000 on “political donations.”

That letter was quickly followed by an amended tax return, again prepared by Conlon, acknowledging the political activity but presenting yet another story: ACU had acted as a cutout, delivering an anonymous donor’s money to a political action committee rather than spending its own money. (It would later emerge from the FEC’s investigation that ACU took a $90,000 fee from the funds as compensation for sitting in the middle of the transaction.)

ACU’s contradictory accounts eventually caught the attention of CREW, which filed a complaint that ACU had made a contribution in its own name on someone else’s behalf, in violation of federal election law; the complaint triggered a two-year FEC investigation. That probe ended in a settlement that required ACU and its counterparts in the transaction to pay a $350,000 fine.

The investigation did not resolve who was responsible for the errors included in ACU’s 2012 tax filings and audit. The identity of the anonymous donor remains a mystery, with the FEC’s efforts to disclose the name tied up in litigation. A federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., held oral arguments in the case last month.

Conlon said he did not recall the ACU controversy. ACU did not respond to a message seeking to discuss the case.

Conlon also stressed to Yahoo News that his client list was broader than the politically connected conservative organizations. In fact, he has, according to public records, prepared taxes for Just Neighbors Ministry, a northern Virginia nonprofit that provides legal services for low-income immigrants.

“Most of them aren’t political at all,” Conlon said. “Most are faith-based organizations in the D.C. area.”

Luppe B. Luppen is a lawyer and a writer in New York City. He is @nycsouthpaw on twitter.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Trump asks why Mueller hasn’t interviewed ‘hundreds’ of campaign staffers

George Conway: Republican Party has become a ‘personality cult’ under Trump

Trump administration defends asylum crackdown after judge’s ruling

An American killing: Why did the U.S. Park Police fatally shoot Bijan Ghaisar?

Cory Booker: I will ‘take some time over the coming months’ to consider 2020 bid

PHOTOS: Trump participates in the G-20 summit in Buenos Aires, Argentina