He loved anime, despite its racism. Now Black Kansas City creator tackles that world

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Brandon Calloway grew up loving Japanese anime: the mesmerizing art styles, vibrant music and masterful storytelling.

But certain characters in these cartoons made him feel uncomfortable, downright awkward at times.

“I remember watching ‘Dragon Ball Z’ and seeing Mr. Popo,” says the Kansas City native. “I remember thinking that’s supposed to be me!”

That character, like Jinx in the Pokemon anime, had big red lips, pitch-black skin and questionable mannerisms — minstralized, offensively stereotypical features. (Pokemon has since changed Jinx to be purple, but the other features remain.)

“Kids in other communities is watching it and seeing themselves as Vegeta and Goku (both muscled warriors with dark hair and light skin), but I am supposed to be Mr. Popo?”

Still, Calloway has found more positives than negatives in anime and manga (the genre in comic book form). He and other young Black fans could relate to stories about an underdog with a fighting spirit.

“Feeling like the outcast and that you don’t belong is what resonated with us,” he says.

Now, seeing the rising number of Black fans like him, looking for a story that speaks to them with characters they relate to, he decided to create his own.

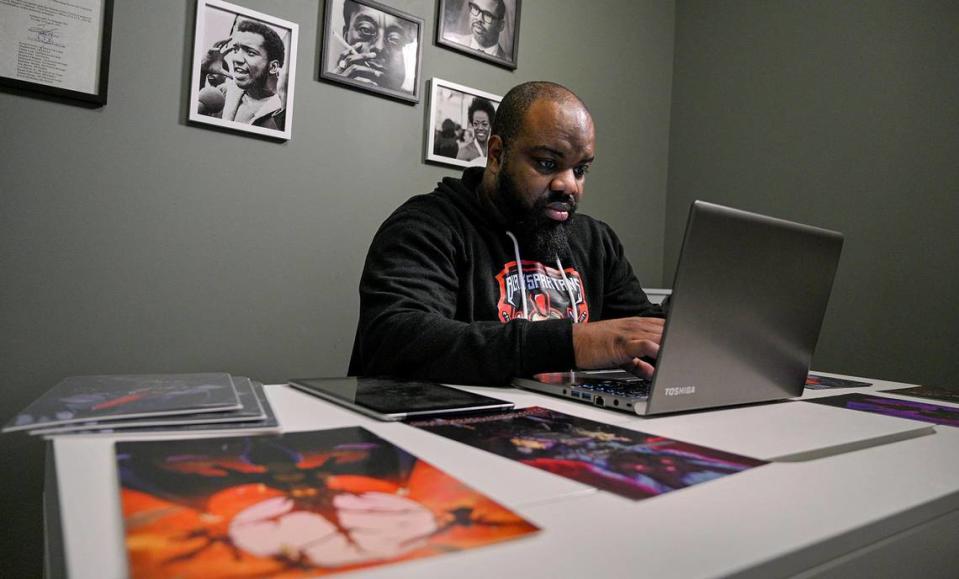

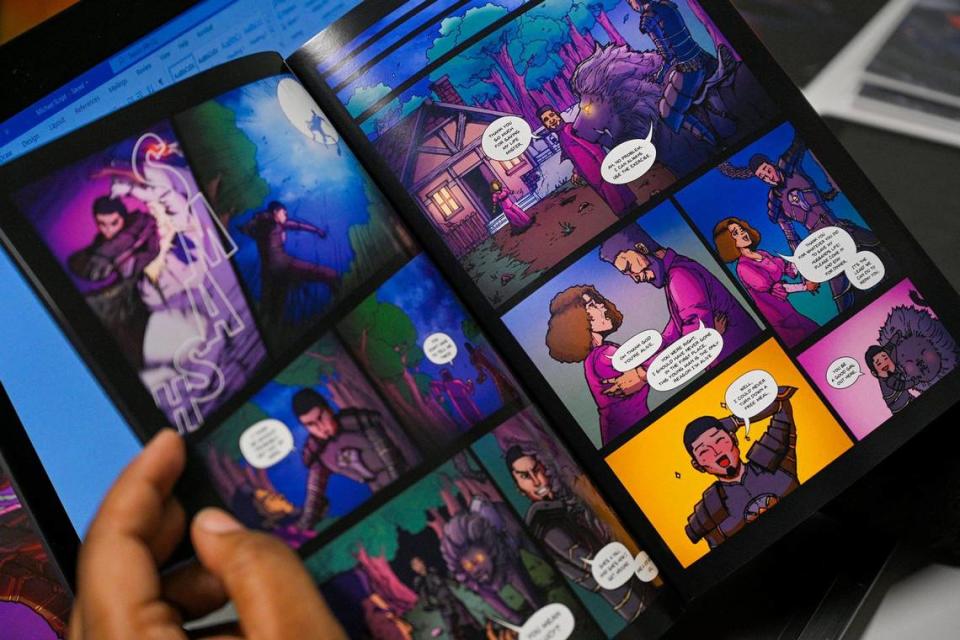

This fall, Calloway, 31, launched “Black Spartans,” a manga set in a feudal land where his titular Black heroes hunt demons.

He has already released two chapters of his story (at darkmooncomics.com), and plans for 200 in a 12-volume series.

Over the past year, Calloway already made a name for himself in the Kansas City urban core via his nonprofit, GIFT, which stands for Generating Income for Tomorrow, created to provide grants to Black entrepreneurs.

While assisting in the dreams of startup Black businesses east of Troost Avenue, Calloway decided to finally pursue his own dream.

Hidden anime passion

Calloway, like many others in the Black community, grew up hiding his love for anime and manga.

Anime was not a recipe for acceptance in an already difficult teen life.

“I used to go to ‘Yu Gi-Oh’ card tournaments every Saturday, but it was something you would never talk about during the week at school,” says Calloway, who graduated from Paseo Academy of the Fine and Performing Arts.

“Young men in Black culture are taught to be hard, so the idea of anime was looked at as childish and counter to that idea of manhood. People won’t just make fun of you for liking anime, it was like a challenge to your Blackness.”

In the early 2000s, Cartoon Network began to air its Saturday night “Toonami,” a block of late-night programming that would become staples of the American anime consciousness, such as “Dragon Ball Z,” “Gundam Wing” and “Cowboy Bebop.”

A few Black characters weren’t overtly offensive.

Japanese creator Shinichirō Watanabe imbued “Cowboy Bebop” and “Samurai Champloo” with elements of jazz and hip-hop, which increased his already stylized appeal. But they were still somewhat stereotypical. (This month, Netflix launched a live-action reboot of “Cowboy Bebop.”)

Then in 2016, American artists Arthell and Darnell Isom, along with animator Henry Thurlow, moved to Japan and founded D’Art Shtajio, the first Black-owned anime studio in the world. They found major success working on massive anime projects, such as “One Piece,” “Attack on Titan” and “Tokyo Ghoul,” as well as creating the anime-inspired visuals for singer The Weeknd’s music video “Snowchild.”

“You are just now seeing more Black creators because more Black people are finally being open about their interest,” says Calloway. “Now we have to go in and take ownership of our image and control our representation if we don’t like how we are being shown.”

He wanted to create his own story with Black characters while still remaining true to the genre and style.

Creating a business

Calloway began the process of learning the trade — exactly what goes into the making of a manga and how to possibly get it off the ground with little to no local anime or manga production in the city. Thankfully the internet university of YouTube gave him a foundation to build on.

Next, he began to contact Black creatives. He planned to write the story, but he needed an illustrator.

“I started coming up with everything in the middle of COVID and knew I wouldn’t be able to promote at comic cons or meet people in the field,” he says. “Then I found my artist and my publisher online and saw how big the online Black fan community was and said I can do it purely this way.”

Over a year ago on social media, he saw the Florida-based, Black owned art collective Macchiato Studios and teamed up with its founders, Hotep Anthony and Roland Broussard.

“He was looking for some people to help bring his vision to life,” says Anthony. “I think he liked the way our work captured the more Eastern dynamic, the vibrancy of our colors, the anime feel.”

The year-old studio, which produces manga and Western comic styles, has already assembled a staff of 10 artists around the world.

Anthony, too, says he was once a closet anime fan, much like Calloway.

“It’s become cool in recent years. It wasn’t until much later in life, like past college, that talking about anime in my life became a normal thing,” Anthony says. “Until very recently, it was looked at as a nerdy. It was uncool.”

The 29-year-old and his partner saw that with more Black fans, there was an untapped market for stories like “Black Spartans.”

“A lot of people don’t really know that the Japanese culture has been really into rap and hip-hop. You see that like with “Devilman Crybaby” (an anime show) that came out a few years ago. They take a lot of our culture and make it their own,” says Anthony. “I like to see us do the same thing, where we begin to have our own anime. Something respectful to Japanese culture but fundamentally Black creations.”

Calloway is proud to be a Black creator but does not want his material to be bogged down with the superficial drama that can come along with minority inclusion.

“There are extra expectations on Black creators all around,” says Calloway. “Because it’s Black it gets tagged as woke. Here are these SJWs (social justice warriors) trying to push diversity for diversity’s sake, and it’s not that. I hope people can look past it.

“Indy white creators get to create something because they enjoy it. I have to explain every creative choice to everyone. My experience as a Black man is different to another Black man, but I have to be the representative for all Black culture.”

Calloway notes that not surprisingly, a fair share of criticism comes from within his own community, literally judging a book by its cover on social media.

“People tell me you need to have more of a message, says Calloway. “I had somebody who looked at it and immediately rated it zero stars. Didn’t read it, just made comments about ‘Spartans’ not being Black and not knowing my history about who the Spartans were. There is an extra pressure all around from people for what you should be doing as a Black creator.”

For Calloway, the main purpose of his work is to bring people together through a shared love of the foreign animation style, no matter the background. Many members of various communities are also just now finding the courage to openly participate in the fandom.

He has seen the unifying power of two fans having a moment to converse over a character or logo on a piece of clothing.

“I have this ‘Naruto’ hoodie,” he says, referring to the popular manga series, “and I have been stopped by random white guys who just want to say they like it, and we always end up having a conversation. I have seen someone with a T-shirt or hat and stopped them.

“I used to wouldn’t have said anything, but now I want people to see it’s OK, and more importantly, it’s cool.”