Like Ted Cruz, Beto O'Rourke had a fiery, charismatic father. The similarities end there.

EL PASO, Texas — In January 1986, an unusual piece of mail arrived at the White House. Addressed directly to President Ronald Reagan, it was a bill for $10 million from the county of El Paso, Texas, a sprawling desert community along the border with Mexico that at the time was one of the country’s poorest cities.

Resembling an actual hospital bill, the statement demanded an immediate payment of $7.5 million for the treatment of “undocumented aliens” who had sought emergency care the year before at R.E. Thomason General Hospital, El Paso’s only public medical facility and the one closest to Mexico. It asked for another $2.5 million for overdue Medicare-Medicaid reimbursements that helped cover bills for the poor — payments that had been frozen amid a dispute between the administration and Congress over proposed federal health care cuts.

Accompanying the bill was a letter from a man no one in the White House had ever heard of. Judge Pat O’Rourke — who was not actually a courtroom judge but the chief executive of El Paso County — warned that Thomason General was in danger of bankruptcy due to illegal immigrants coming from Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, for medical treatment. Required by law to treat the indigent, regardless of their citizenship status, the hospital was losing money caring for patients from whom it could not collect payment.

Among the patients were pregnant women who came to the hospital to give birth, making their babies U.S. citizens. Illegal aliens, as O’Rourke referred to them, were streaming across the border seeking jobs and a better life as well as medical care, and the county’s health and social services budget was being stretched to the limit. “The basic rules are all being broken,” O’Rourke told the Los Angeles Times. “It is no longer mutually beneficial to be neighbors because the balance is changing. Now we’re just importing their poverty.”

Though he was critical of the negative economic impact of immigration, O’Rourke was sympathetic to Mexicans. The economic situation across the border was dire, the health care inadequate — and O’Rourke, a Democrat who was socially liberal but fiscally conservative, thought the U.S. hadn’t done enough to help its southern neighbor. If he were living over there and one of his kids were sick, he told CBS News, “I would take my child, and I would walk across that six-inch river, six inches deep, and I’d save my child’s life. I’d do the same thing these people are doing.”

If the name O’Rourke is familiar, it’s because his son, Rep. Beto O’Rourke, is a rising Democratic star who is giving Sen. Ted Cruz a run for his money in one of the most closely watched Senate races in this election cycle. And although Beto rarely mentions his father during the campaign, observers of Texas politics say he has inherited much of his iconoclastic temperament and volatility from his legendary father.

El Paso’s fate was intricately aligned with Juarez’s — culturally and economically. “We are all Mexicans in the valley,” O’Rourke often said. But his city was simply not equipped to deal with the looming economic and foreign policy disaster on its doorstep. It was the federal government’s duty to regulate immigration, he told Reagan, so it should be the federal government that should bear the costs incurred by illegal immigrants. Angered by Washington’s inattention, he told a friend, businessman Jack Maxon, “I’m just going to send Reagan a bill.”

The judge’s message to the White House made national headlines. It thrust El Paso — and O’Rourke — into the middle of a heated national debate over illegal immigration, culminating in Reagan’s landmark immigration bill later that year.

While the money ultimately was never paid, O’Rourke got credit for raising the issue and trying to help his city.

“There were two things you couldn’t dispute about Pat: He loved El Paso, and he had guts,” said Bill Tilney, a former El Paso mayor and foreign service officer who was in charge of the U.S. Consulate in Ciudad Juarez in the mid-1980s and who worked with O’Rourke on cross-border issues. “He didn’t have his finger in the air, trying to judge which way to go. He tried to do what he believed was right.”

Now his son confronts Cruz, who has made his own father, a Cuban immigrant, a central figure in his political career. The story of Rafael Cruz, his religious rebirth and pursuit of the American dream, was the emotional and inspirational backbone of Ted Cruz’s campaign for the Republican presidential nomination in 2016. As Cruz seeks reelection to the Senate, his father has emerged as one of his key surrogates on the campaign trail in Texas.

But Beto O’Rourke rarely mentions his father, who died in a cycling accident in 2001. The congressman’s stump speech doesn’t focus much on his personal life story — perhaps because growing up as the son of politician is less gripping than the tale of Cruz’s immigrant father.

But those who knew Pat see his influence all over his son’s insurgent campaign. Notwithstanding political and certain stylistic differences between father and son, Beto O’Rourke’s relentless energy, ability to connect with average people and his tendency to operate more on political instinct than conventional wisdom remind many people of his dad.

“It’s like sometimes looking at his dad in the mirror from my vantage point,” said Felipa Solis, a former El Paso newscaster and O’Rourke family friend whose late husband, Mickey, served on the county commission with Pat O’Rourke.

But as he has charted his own career in public service and now seeks to become the first Democrat elected statewide in Texas in more than two decades, Beto O’Rourke has tried hard to avoid the “son of” label. In an interview, he is careful to note that his dad did not seek to mold him as a politician or push him to run for office “in any real serious way” — though he acknowledges like many sons he is in some ways carrying on his father’s dreams.

“Your dad’s part of you, forever, and is in your wiring through your DNA and just the impact your dad’s had on you,” Beto O’Rourke said. “He definitely lives through me in many ways, and of course, in many ways, I am my own person.”

*****

News stories about Beto O’Rourke’s rise frequently mention his background as an Irish-American who got his political start in a largely Hispanic border city.

And that’s what they were saying decades ago about his father. Before he entered politics, Patrick Francis O’Rourke was an entrepreneur, a third-generation El Pasoan whose family had relocated to South Texas decades earlier to help build the railroad.

Like his son, Pat grew up in a comfortable household. His father, John Francis O’Rourke, known as Frank, worked as a spokesman for Reynolds Electric and Engineering Company, an El Paso-based contractor that helped build the nation’s first nuclear weapons testing sites in neighboring New Mexico. After graduating from University of Texas at El Paso, where he majored in business administration, Pat relocated to southern California, where he was living when his father died suddenly in 1966.

Pat moved back to El Paso, where in 1971 he married Melissa Williams, whose prominent family owned a furniture store, Charlotte’s. A little over a year later, Pat and Melissa welcomed their first child, a son named Robert Francis O’Rourke — named after Melissa’s father, Robert, and Francis, the middle name given to all of the O’Rourke men.

But from the day he was born, Pat called him Beto, a nickname to distinguish his son from his grandfather, but also a nod to the Mexican heritage of El Paso, where Pat had grown up speaking the Spanish he picked up from his Mexican friends. When their second child, a daughter named Charlotte, was born in 1977, Pat called her Carlotta — a nickname Beto still uses for his sister. (In 1980, the O’Rourkes had a third child, Erin, who was born with a mental disability and has maintained a lower profile than the rest of the family, though she has occasionally attended political events with her brother.)

“I spoke Spanish before I spoke English,” Pat O’Rourke told CBS News in 1986. “When I was a kid, I’d get on a streetcar and go to Juarez and go to the cine, the movie, over there. That’s my community. … It’s all one community.”

In 1978, Pat decided to run for a seat on the El Paso County Commission — a major race for someone who was a political neophyte. The decision, Maxon recalled, seemed to come “out of the blue.” “Nobody had any idea he was going to get involved in politics, and he just did it,” he said.

The odds weren’t against him only because of his lack of political experience. Even back then, El Paso politics was dominated by Hispanics. And while he spoke Spanish fluently and was as comfortable hanging out in the barrio as he was mingling among the city’s white elite, O’Rourke was unmistakably Irish American — “a kind of Tip O’Neill of El Paso,” Maxon described him.

Pat suspected it would be used against him. And so he embraced it. One morning during that campaign, Bonnie Lesley, who had met O’Rourke during her work with the El Paso Political Women’s Caucus and was running his campaign, was driving to work when she got stuck in a traffic jam. At first she thought it was an accident, but as she got closer, she saw a man on the side of the road dressed in an elf suit waving at cars and handing out fliers. In shock, she realized it was O’Rourke, campaigning on St. Patrick’s Day.

Stunned, Lesley rolled down her window. “Pat,” she shouted. “What are you doing?” O’Rourke grinned. “I’m having more fun than I’ve ever had,” he told her. “And people love it!” Across the way, she noticed a pack of television cameras, filming the scene, and other drivers laughing.

“He just had an instinct about how to connect with people. … It wasn’t just work and drudgery and worry and fussing the way a lot of campaigns devolve into. It was fun. He had fun,” Lesley recalled. “Pat O’Rourke was the best candidate I’ve ever worked with. The best candidate I’ve ever seen —except for Beto.”

O’Rourke won the race, to the surprise of political insiders. And four years later, in 1982, he set his sights on a higher seat, county judge — a position that would effectively put him in charge of El Paso County government. His opponent was a well-known Hispanic city councilman who had been entrenched in city politics for years. The race soon got ugly — in ways that are surprisingly similar to the attacks that Beto O’Rourke has faced in his race for Senate.

During the campaign, Pat O’Rourke’s opponent questioned his patriotism, telling voters O’Rourke had years earlier burned an American flag at an El Paso political rally — although he offered no proof. O’Rourke angrily denied the charge and sued his opponent for slander, a lawsuit that was eventually settled out of court.

His opponents also tried to use his penchant for using profanities against him. At one point, Pat was hauled into court on a charge of disorderly conduct after he cursed at a security guard at a local park. O’Rourke apologized, blaming his fiery Irish blood, and said he was trying to curb his tongue — just as his son, Beto, has said on the campaign trail this year, amid attacks from Cruz over his penchant for using occasional profanity on the stump.

Beto O’Rourke has attributed his blue streak (“We have to win this f***ing election!” he regularly tells voters) to a lack of discipline. But he also admits it’s probably an inherited trait from his dad, “a world-class swearer” whom he said could string together so many variations of four-letter words in general conversation that it could shock even the most profane people.

“That was my dad,” Beto O’Rourke said.

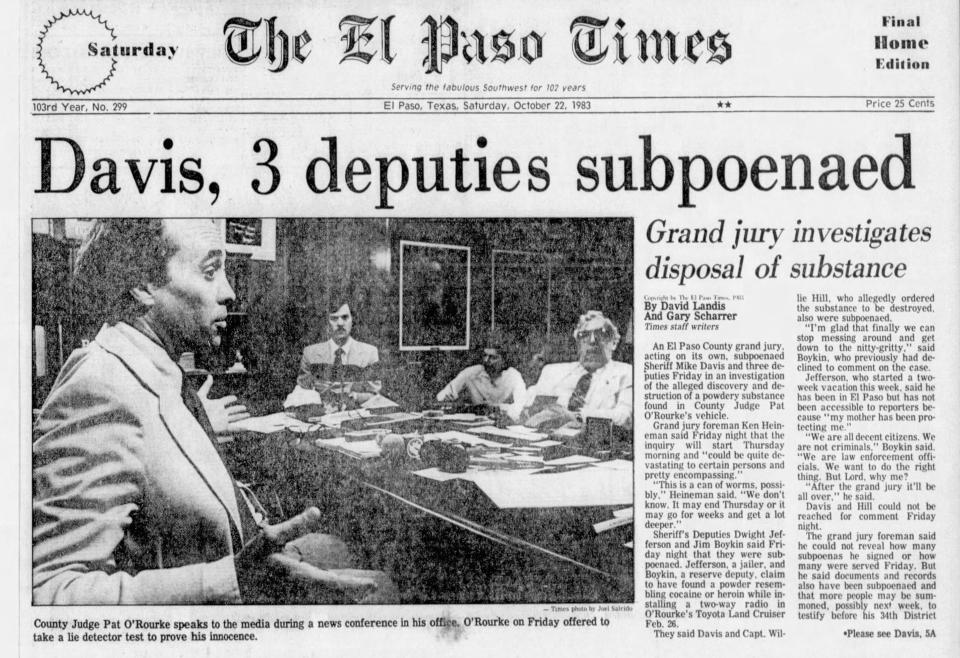

Pat won the race for judge, but he was soon caught up in controversy. In early 1983, while installing a police radio in O’Rourke’s car, two sheriff’s deputies discovered a condom half full of a white powder in the vehicle’s glove compartment. A superior ordered them to flush it down the toilet—later explaining that he believed the substance had been planted, possibly by one of O’Rourke’s political enemies.

O’Rourke insisted he had “no earthly idea” what the substance was or how it had gotten into his glove box. He offered to take a lie detector test to prove his innocence and pointed to his relentless health regimen as a cyclist who rode thousands of miles around the country every year and a runner who spent his mornings before work jogging around downtown El Paso. He couldn’t do that and be a drug abuser, O’Rourke told reporters.

When a grand jury was convened over the incident — looking into police misconduct, not O’Rourke’s — the judge worried about long-term damage to his reputation. The whispers had already “set me back,” O’Rourke told reporters in 1983, and no matter what the findings were, he’d likely never be truly cleared since the evidence had been destroyed. “I am very concerned about what this may do to my family (and my) ability to do business in the county,” he said.

He was right. Though Pat remained popular with his constituents, rumors of drug abuse and excessive drinking dogged him for the rest of his life — and decades later, have become fodder for conservative blogs digging for dirt on Beto O’Rourke and his family. But those close to Pat wave off the allegations as nothing but gossip. “Anyone who knew Pat knows that’s just not who he was,” a friend said.

Pat O’Rourke could be eccentric. Bruce Lesley, who was O’Rourke’s top assistant when he was county judge, recalled his boss occasionally showing up at meetings in his jogging clothes, sweaty from a workout, startling people who hadn’t met him before. “But he was such a people person and had this great, huge personality. It would just take up all the room,” he said. “They didn’t always get along with him, but everybody loved him.”

O’Rourke was a relentless campaigner and fundraiser for himself and other Democrats. Though his wife, Melissa, was a registered Republican, their home in the hills near El Paso’s famed Rim Road became a political salon of sorts, hosting Pat’s famous Democratic friends, including then Texas Gov. Mark White and Jesse Jackson — who would later tap Pat as Texas co-chair of his 1988 presidential campaign. “Black people love Pat O’Rourke!” a Jackson aide said at the time.

When the elder O’Rourke roamed around town, he often took along his young son, Beto, giving him a first-hand education in his future career. “He had this real joy in public life, in meeting people and representing people,” Beto O’Rourke recalled. But he admits he didn’t find the same kind of enjoyment in it. “In some ways, I really hated it,” he said.

While Pat was charismatic and outgoing, his son was reserved, more like his mother. Pat would nudge Beto, suggesting he go say hello to “this person or that person,” his son recalled. “It was the kind of stuff you don’t want to do when you are 10 years old, unless you were really into that. And I wasn’t. I was an awkward and shy kid, so it was the last thing I wanted to do, but now I can look back and bless my experience in it.”

*****

After eight years in county office, Pat O’Rourke didn’t run for reelection, telling friends that he didn’t believe in politics as a career. In 1987, he returned to the private sector, where he worked as a consultant, dabbled in real estate and tried to launch a few new ventures over the next few years. None of them were very successful.

In 1992, Pat, seeking a political comeback, launched a bid for Congress — but this time, he ran as a Republican, shocking many of his friends and political allies. Running as a Republican in deeply Democratic El Paso was a political suicide mission, even for someone as well known and respected as O’Rourke. Explaining his change of heart, he said Democrats were hostile to business and had abandoned fiscal restraint. “The party left me behind,” he said. O’Rourke lost that race and two others in later years.

Beto O’Rourke didn’t talk to his father about his political transformation. In 1988, two years after Pat had left public office, Beto, then 15, transferred from El Paso High School to Woodberry Forest, an all-male boarding school in Virginia. Beto O’Rourke admits he left El Paso largely to achieve some distance from his father.

Part of it was the typical teenage experience of children at odds with their parents. While they had bonded over a mutual love of nature — Pat had been taking his kids, since they were babies, on hikes through nearby national forests and on long-distance bike rides — they had less and less in common as Beto entered his teenage years. Pat was outgoing, Beto was shy. While Pat was obsessed with politics, Beto wasn’t interested. He sought refuge in the burgeoning punk scene in El Paso, something his father, a country music fan, didn’t understand.

In the midst of his own midlife crisis, Pat clashed with his only son, who for his part struggled to get out of his father’s shadow. “Pat consumed all the oxygen in the room and had high expectations for his son,” a family friend said. “And while Beto loved his dad very much, he didn’t have room to breathe.”

“He was this larger than life personality and presence, and we did not always get along or see eye-to-eye, even at a young age,” Beto O’Rourke said. “I knew it was going to be better for me, better for everybody, to be out of that house.”

Moving first to Virginia and then to New York, where he attended Columbia University, Beto O’Rourke did not expect to return to El Paso. After graduating in 1995, he stayed on in New York, where he worked odd jobs and considered a career in book publishing. But in a path that echoes his father’s own journey, in 1998, O’Rourke felt drawn back to his hometown, finally seeing the potential his father had always seen in El Paso.

Pat was there waiting. “In a lot of ways, I think Pat did what he could to help El Paso flourish because he wanted to make it a better city for his kids,” said Felipa Solis. “He believed so much in Beto, knew how smart he was from a young age. I think he was always hoping he would come back and do his thing in El Paso.”

Not long after he returned to Texas, Beto O’Rourke launched his own company, Stanton Street—part technology company and part online newspaper. His dad, he said, was a key player in getting it off the ground. He advised on the business side and wrote an online column. It finally brought father and son close, in spite of their differences.

In summer of 2000, Pat O’Rourke, who had done several cross-country bike rides, launched one again — this time on a recumbent bicycle, where the rider sits in a reclined position close to the ground. He maintained a diary of his journey, from Oregon to New York, on the Stanton Street website, where he wrote of the people he encountered and offered up political ideas for El Paso based on what he’d seen and heard in other cities.

A little over a year later, he was killed on a road outside El Paso, riding the same bike as he trained for another cross-country trip. He was just 58. His family was devastated — none more than his son, Beto, who stepped up to deliver the eulogy at his father’s funeral and, to some, began to embrace his role as his father’s heir apparent. St. Patrick’s Church, where the memorial was held, was packed with hundreds of people, not just the political elite but everyday people with whom his father had interacted, a sight that stunned and humbled his heartbroken son.

“One of the most interesting things of my adult life is how many people have come up to me to tell me that my father was their best friend,” Beto O’Rourke said. “That tells you how extraordinary he was. … He loved being alive, he never wasted a minute, just loved being with people and working with people.”

After Pat’s sudden death, his friends saw a change in Beto O’Rourke. He took up an interest in politics, and after considering a run for county judge, his dad’s old job, he ran for city council, taking on a well-known incumbent and mounting the same kind of aggressive ground campaign that had helped his father win. He knocked on thousands of doors, including in the barrio, going to places where politicians did not always go — the same blueprint he’s embraced in his unlikely race for Senate. The shy son of Pat O’Rourke was suddenly as charismatic as his father.

“I think Pat would be astounded by how well Beto has done … but not surprised. He always knew the potential was there,” Jack Maxon said.

Beto O’Rourke sometimes struggles to talk about his father. On stage last year at the Texas Tribune festival in Austin, the congressman was asked how his father’s time as a public servant had informed his own service. The lawmaker choked up and could barely answer. Though it’s been more than a decade since his father’s death, the pain is still there, he said in an interview.

Two weeks ago, the congressman was home in El Paso. It was his first morning off in weeks, coming after more than a month of criss-crossing Texas in a rented pickup truck followed by trips to New York, Washington and Los Angeles to raise money and publicity for his unlikely campaign. He had barely seen his wife, Amy, and their three kids. He was emotionally and physically exhausted, but there was no time for a break. He had to fly to Houston for a town hall and then on to Dallas, where he would meet Ted Cruz on the debate stage. He suddenly felt drawn to visit his father’s grave.

O’Rourke couldn’t explain why. Something was pulling him, and he just needed to go. So before his flight, the congressman drove out to the cemetery on the western side of the city, not far from the road where his father was killed, to that old cemetery nestled in the desert valley not far from the Mexican border. It was the first time he’d been there in a couple of years, the first time since he had the wild idea of running for Senate. He thought about the strongest memories he had of his dad, of their backpacking trips, of walking in the mountains, just the two of them and nature. He thought about the person his father was and wondered what he would be thinking about all of this.

“He was the most fiercely independent person, to a fault. He did not care who he pissed off and was always focused on doing the right thing,” O’Rourke said. “He found such joy in [public service], and that was such a powerful example for me: Find the joy in this. Find the joy in this and whatever you do.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Clinton aide: We didn’t recognize ‘full scope’ of Russian interference on social media

The go-between in the Trump Tower meeting offers clue to claim in dossier

Was Kavanaugh saved when the GOP abandoned its ‘female assistant’?

Ten years ago, Washington put politics aside. Could that happen today?

Photos: Deadly earthquake and tsunami kill hundreds in Sulawesi, Indonesia