Kittery's 375th: Rock Rest was 'an oasis' for 20th-Century Black travelers

This article is part of a monthly series celebrating Kittery's history, as Maine's oldest town counts down to its 375th birthday.

Kittery has long been celebrated for its deep and storied history. One aspect of its past, however, remained under the radar for many years.

In the mid-20th century, the residence of Hazel and Clayton Sinclair was known to a number of African-American motorists as Rock Rest – a rare place of comfort where they could feel welcomed while traveling through Maine.

While the American South is generally perceived as the region most hostile to Black citizens during this era, Kittery resident Bob Sheppard notes that racism was not confined to any particular corner of the country.

“In other words people who looked like me, or members of my family could not stop spontaneously for gas, food, groceries or even clothing in many parts of the country, including New England,” Sheppard stated this week. “Rock Rest was an oasis, a break from the hostility, the indignities and downright hostility experienced by Blacks who had the means to travel in America.”

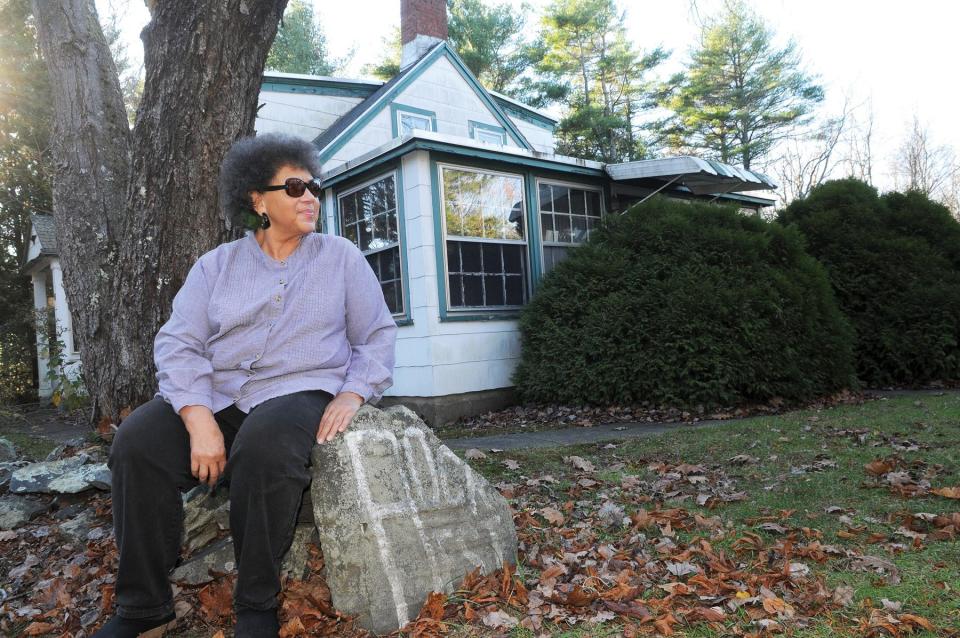

The Sinclairs are no longer with us, but their story has gained new attention in recent years. This past June, two stone markers – one in the popular Foreside area and one at the private property on Route 103 where Rock Rest was located – were unveiled in Kittery as part of the Seacoast’s Black Heritage Trail.

A remarkable cookbook just published by Kittery resident Betsy Wish to commemorate the 375th birthday of Maine’s oldest town features an entire section devoted to Rock Rest, and the legendary recipes of Hazel Sinclair. Wish was inspired to do so after seeing the site mentioned in the 2020 PBS documentary “Driving While Black: Space, Race and Mobility in America.”

Sheppard helped put together a Zoom presentation hosted by Lane Library in Hampton, New Hampshire, last year to share the story of Rock Rest. He actually met Hazel while working as a broadcast journalist for New Hampshire radio station WHEB back in the 1980s, as part of a piece about the history of the Seacoast NAACP.

“I was invited to her home experiencing a taste of her gracious hospitality, coming away with a sense for the role she and her husband played in the period before passage of the Civil Rights Act,” he explained.

“Hazel and Clayton Sinclair made sure their guests felt appreciated, they were served wonderfully prepared home-cooked meals, served on fine china, and had the chance to socialize with fellow travelers from New York, Philadelphia, and Washington DC.”

More: 'Creating this tangible life' African American guesthouse pieces in Smithsonian museum

The story of Clayton and Hazel Sinclair

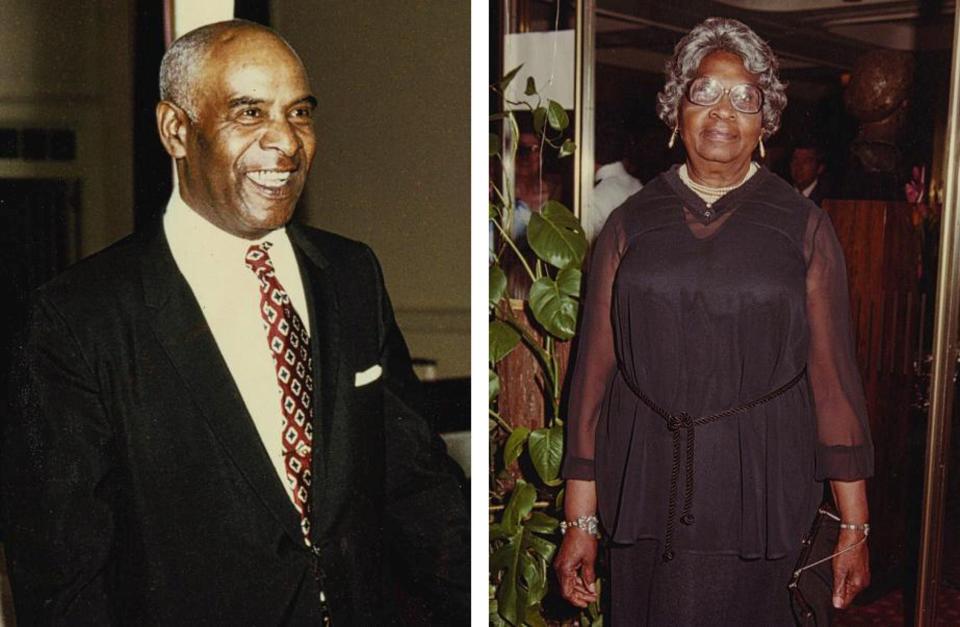

The story of the Sinclairs is, in many ways, reflective of The Greatest Generation. Prior to the Second World War, Clayton Sinclair came to the Seacoast from New York City as a chauffeur for a wealthy family descended from the late literary giant William Dean Howells, who had a summer home in Kittery Point. Hazel was employed in the Seacoast as a maid and cook. They met in the summer of 1936 and married the following year.

The property they originally purchased on Route 103 was “little more than a shack,” Hazel later told interviewers. But they renovated the home, rebuilding the chimneys and updating the kitchen. Clayton gained employment at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, but after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 he enlisted in the Navy. Hazel got a job at the shipyard during the war, serving as a woodworker’s helper.

After victory by the Allies ended the war, the Sinclairs opened up their home as a guest house. Gradually, other rooms and outbuildings had to be added as its popularity spread.

As Sheppard points out, there was a “growing Black middle class” in America after the war, and families wanted to share the joys of exploring the country on the open road. Unlike white families, however, they were not always welcomed at restaurants and hotels they happened to pass along the way.

“Black travelers could be denied service without warning and with no legal recourse,” according to the memorial markers unveiled in Kittery this summer.

Sheppard notes there were similar Maine homes in York, Ogunquit and Old Orchard Beach during this time.

“While they were not all included in the 'Green Book for Negro Motorists,' people learned of their hospitality by word of mouth, and Rock Rest was normally booked for the entire summer well in advance,” he explained.

The Green Book – part of the basis for the popular 2018 Academy Award-winning film of the same name – advertised American road locations where Black travelers would be accepted.

The Sinclairs could accommodate up to 16 guests at a time. Most stayed for a week, sometimes two, and would make day trips throughout the Seacoast area. Guests would also play croquet and horseshoes there on the property. But one of the keys to the site’s popularity was Hazel’s cooking.

Betsy Wish said last week she drove past their former home for many years without knowing about its history. She first became interested after seeing the 2020 PBS documentary based on historian Gretchen Sorin’s book “Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights.”

When Wish decided during the pandemic to put together an historical cookbook as part of Kittery’s yearlong 375th birthday celebration, it seemed natural to include Rock Rest.

“Why would I not want to include the Sinclair Home in the historical cookbook?” she said. “Rather than a page devoted to Hazel’s recipes, it was obvious to me that they deserved at the very least, a segment devoted to both Hazel and Clayton, bringing Rock Rest to our attention.”

The cookbook, “Kittery’s Maine Ingredients,” shares the recipes for Hazel’s famous carrot “copper pennies,” fudge (which calls for 3 cups of sugar), caramel ice cream, date bars, clam pie, two-egg cake and Maine State potato pancakes, among other delicacies. Wish also describes how Hazel was a popular caterer in town, and provided dishes for local church events.

But the passage also notes that even residents who knew the Sinclairs were not aware of what was happening at Rock Rest, or that African-Americans could be prohibited from lodging or dining locally.

“Rock Rest played a valuable role in Kittery’s history during the Jim Crow Era,” Wish said recently. “By providing African Americans with a place to vacation when they were not permitted to stay elsewhere on the Seacoast, Hazel and Clayton made the unimaginable possible.”

Clayton Sinclair a founder of Portsmouth NAACP; Hazel active in League of Women Voters

Clayton served on Kittery’s Appeals Board and was a founder of Portsmouth’s chapter of the NAACP. Hazel was a member of the League of Women Voters, and both attended People’s Baptist Church in Portsmouth. Wish states in her cookbook that Hazel’s voter registration certificate is now with the University of New Hampshire archives, as are her hand-written recipes, the guestbooks of Rock Rest, newspaper articles, and letters. This is where Wish conducted most of her research.

“I suppose the bottom line is that I felt I’d discovered a genuine treasure when I found the file containing Hazel’s recipes,” she said. “Once I started researching Rock Rest, it was hard to know when and where to stop.”

Clayton died in 1978, not long after the Sinclairs ceased operating their home as a guest house. Hazel, born in 1902, died in 1995. They kept Rock Rest going for more than three decades.

Today, the home is a private residence. It is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

“As one of only a few African American guest houses in the state, Rock Rest enjoyed considerable success and attracted vacationers from across the country,” the 2007 National Register nomination application declared.

Additionally, the stone markers now located in Kittery – appropriate for a place known as Rock Rest – were unveiled this year during events hosted by the Seacoast NAACP Youth Council and the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire, including a ceremony held in Wallingford Square’s Second Congregational Church. Black Heritage Trail founder Valerie Cunningham, a local advocate and historian, worked at the guest house for two summers as a teen. She grew up as a family friend of the Sinclairs and referred to the Rock Rest matriarch as “Aunt Hazel.”

Places like Rock Rest “meant that Black folks could plan to take a trip,” Cunningham told the Herald in 2020.

To be clear, there were officially no “Jim Crow” laws in Maine and New Hampshire even before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but it was not uncommon for establishments to refuse service to those they did not wish to serve. Keeping the story of Rock Rest alive may help ensure this history is not forgotten.

“It's difficult to imagine, but it wasn't that long ago when access to businesses and public accommodations, things we all pretty much take for granted today, was limited due to the color of your skin,” Sheppard said.

Several events are taking place in Maine’s oldest town this year. Information: kittery375th.com

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: Rock Rest in Kittery, ME 'an oasis' for 20th-Century Black travelers