44 years after conviction, Freedom Rider Sala Udin is pardoned by Obama

President Obama’s decision this week to issue 78 Christmas season pardons — the most of his presidency — should have special meaning for veterans of the civil rights movement.

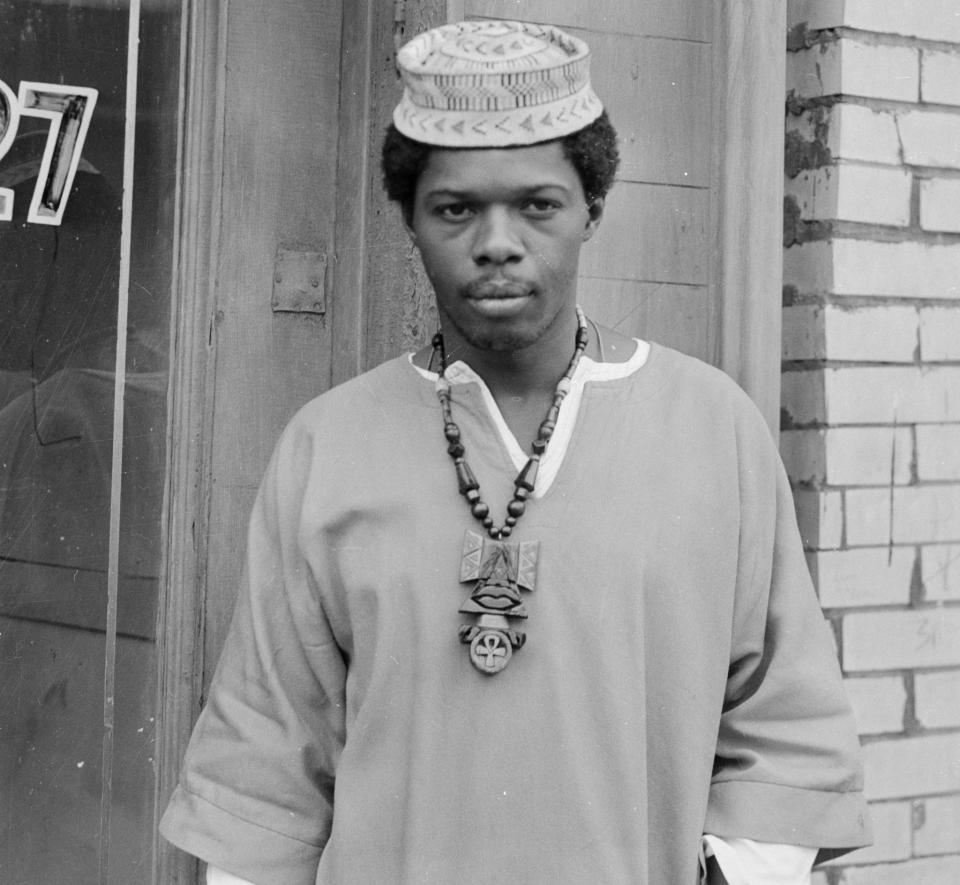

Among the recipients was former Pittsburgh City Council member Sala Udin, a onetime Freedom Rider who was beaten up registering voters in 1960s Mississippi. But Udin had been haunted for decades by a criminal charge that grew out of his youthful activism: Driving fellow protesters home from the South, he was stopped for speeding in Kentucky and arrested after police found an unloaded shotgun and a jug of moonshine in the car.

“I’m ecstatic,” Udin emailed Yahoo News shortly after he got the call from his lawyer that his long-languishing bid for a pardon had finally been granted by Obama. After waiting patiently for years, Udin had all but given up hope. Only days earlier, amid reports that Obama was contemplating a final round of pardons, Udin had told a friend: “I refuse to allow myself to be optimistic because I don’t want to risk the disappointment. It’s not going to happen.”

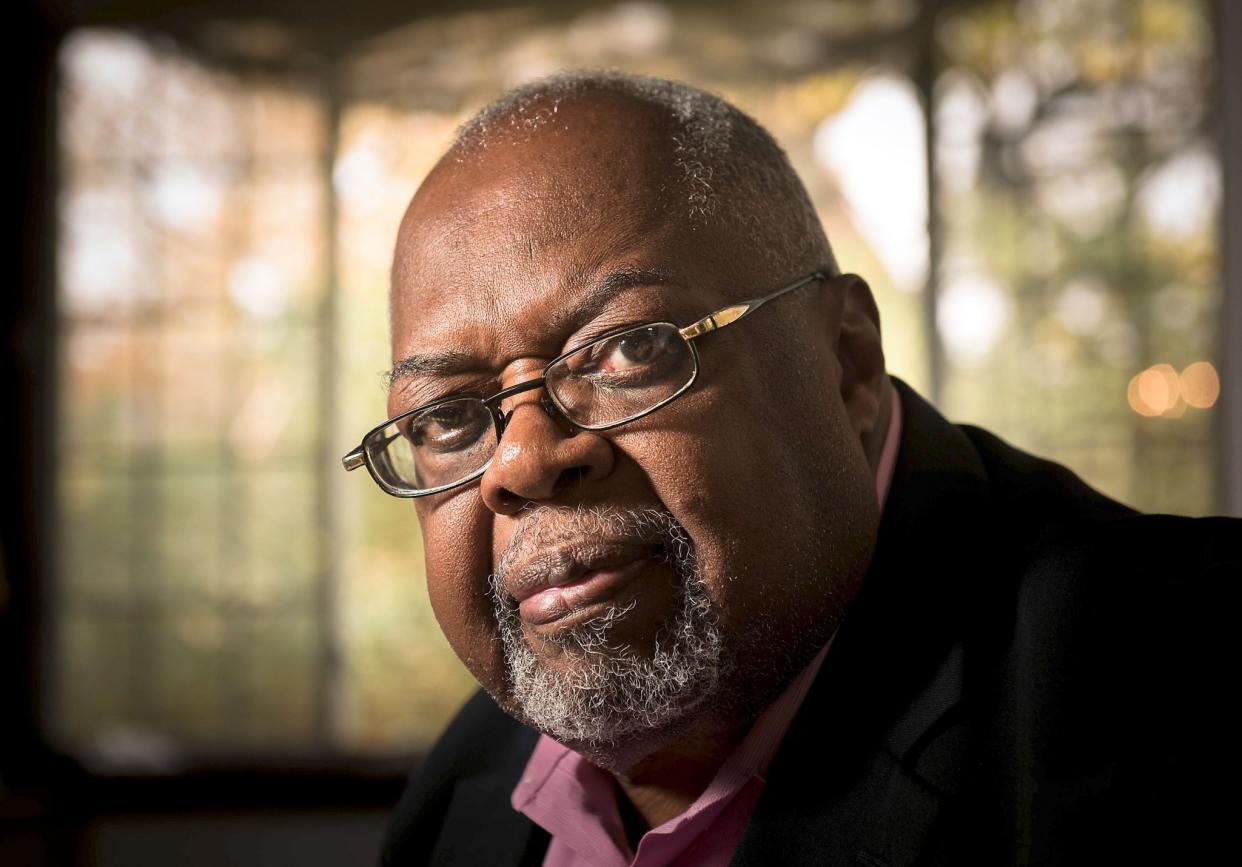

Udin, 73, was the subject of a Yahoo News story last year that highlighted Obama’s relatively stingy record of using his constitutional powers to pardon criminal offenders; one critic even called him a pardon “Grinch.” At that point, Obama had issued fewer pardons than any president since James Garfield. (This is separate from Obama’s commutation of sentences, another of his broad clemency powers and one that he has used liberally to reduce the lengthy prison terms of nonviolent drug offenders — a key part of his administration’s initiative for criminal justice reform. Obama separately commuted the sentences of 153 such offenders Monday.)

But Udin had seemed a perfect candidate for a full pardon — a “poster boy” applicant, his lawyer, Margaret Love, said. In his youth, Udin (who changed his name from Samuel Howze) enlisted as a Freedom Rider for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. His assignment was to register black voters in the Mississippi Delta. In doing so, he faced intimidation from local residents and hostility from all-white police forces. “I was beaten up pretty bad and thought I was going to die,” Udin said last year, describing an incident in which he was pulled over and ordered to “get out of the car, n*****!”

In 1970, while driving back from Mississippi, Udin was stopped for speeding outside Louisville, Ky. An unloaded rifle was found in the trunk of his car (along with that jug of Mississippi moonshine.) He was charged and convicted in 1972 of carrying a firearm across state lines and spent eight months in prison.

Udin always acknowledged his guilt, but with a proviso: “At that point, although I was previously committed to nonviolence, I concluded that if I was trapped on some lonely, dark road in the South and confronted by Klansmen who threatened to kill me, I would be prepared to defend my life,” he wrote in his petition for a pardon to the Justice Department. “I concluded that I would rather be caught by the police with defensive weapons than to be caught by the Klan without them.”

Whatever the explanation, there was little dispute that Udin had gone on to live an exemplary life: He founded an African-American Culture Center in Pittsburgh. He served three terms on the Pittsburgh City Council (from 1995 to 2006), spearheading the creation of the city’s police civilian review board.

And yet, Udin — who had campaigned for Obama and gave him a $500 contribution in 2007— had heard nothing on his plea for presidential mercy for years, causing him endless frustration. Maybe, a reporter suggested, his small donation was the problem: The White House, averse to any whiff of potential scandal, might have feared that a pardon for Udin would look like a favor for a campaign contributor.

“I don’t want to say or do anything that would cause a problem for President Obama,” Udin said then. “I love him. If that’s the reason, I’ll accept it. I just don’t want it to be for any other reason.”

When first contacted about Udin’s case, a spokeswoman said last year that the White House doesn’t discuss the merits of individual cases. But White House counsel Neil Eggleston said yesterday Obama’s pardons and commutations “exemplify his belief that America is a nation of second chances.”

Forty-four years after his civil rights era conviction, Udin on Monday got his second chance. Pennsylvania Democratic Sen. Bob Casey, who had written Obama on Udin’s behalf, said the pardon was “part of how our nation must reconcile with injustices committed against civil rights activists.” Udin, for his part, was “floating on cloud nine,” he told his hometown paper, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, on Monday. “My wife and I just hugged and thanked God,” he added in an email to Yahoo News. “It’s a burden relieved from decades of carrying around the tag-line, ‘convicted felon.’ Now they have to add, ‘PARDONED ex-felon.’”