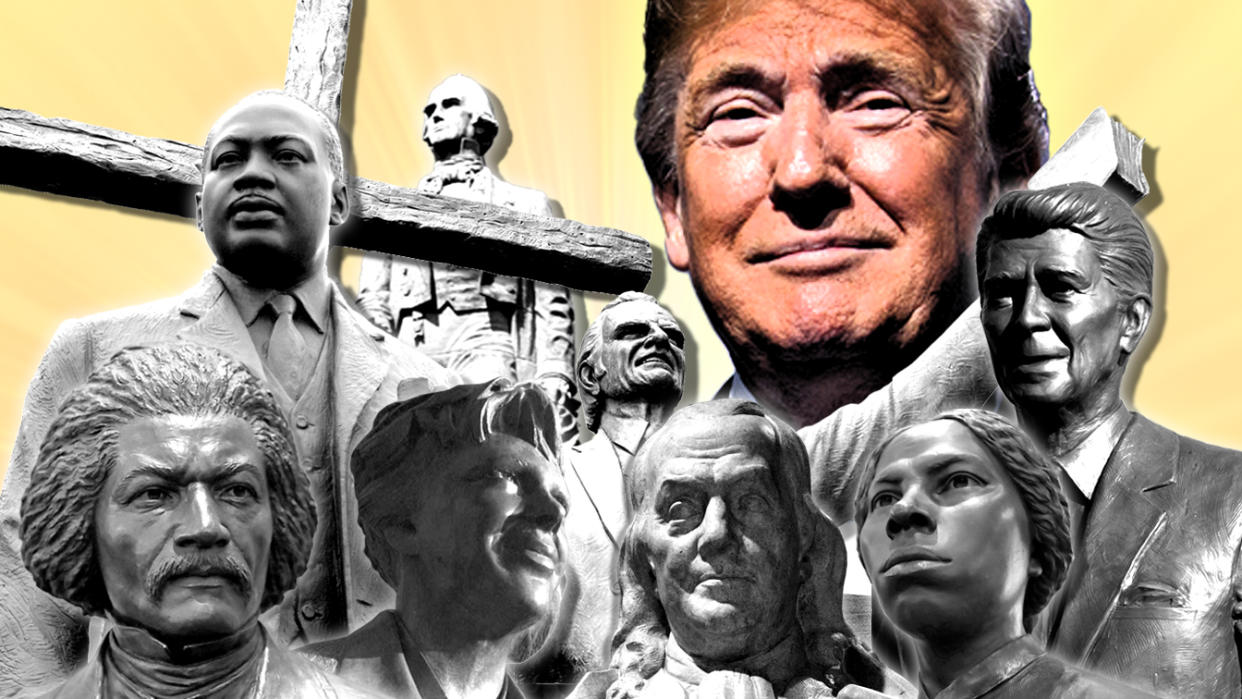

Don't count on ever seeing Trump's 'Garden of American Heroes'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Call me cynical, but I have a feeling the National Garden of American Heroes announced by President Trump on Friday will never get off — or into — the ground, even if he doesn’t put his son-in-law in charge of it.

That is partly, of course, a recognition of the incompetence of Trump’s administration, which has presided over an epic public health disaster and whose signature border wall initiative, guided by Jared Kushner, is proceeding at the rate of approximately 1 mile per year of new construction, not counting upgrades to existing barriers. That is a poor record on which to begin a project that even if it began tomorrow would stretch well into the next administration, or beyond: The deadline for completion is “the 250th anniversary of the proclamation of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 2026.”

But it also reflects my own experience, as I imagine dragging my family to look at a collection of patriotic statues. (“Look, kids! It’s ... Henry Clay!”) The spate of iconoclasm that has erupted on American streets, plazas and parks and has brought down not just Robert E. Lee but George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and even seemingly unambiguous figures such as the abolitionist Matthias Baldwin makes a tempting target for Trump, but this might not be the best ground on which to fight his side of the ongoing culture wars by taking a stand against the “assault on our collective national memory.”

But his impulse is understandable. Establishing an official United States Hall of Fame will secure the reputations of Betsy Ross and Benjamin Franklin from the changing political winds, no less than the one in Cooperstown, N.Y., preserves for the ages the memories of Ted Williams and Roberto Clemente. Putting the statues all in one place under the eye of the National Park Police will keep them safe from mobs seeking to “desecrate our common inheritance.” And stipulating that the monuments must be “lifelike or realistic representations of the persons they depict, not abstract or modernist representations,” seems intended to ensure that they will reflect the aesthetic sensibilities of the middle class, which Trump appears to share. It must have been shocking for him to wake up in the White House on his first day as president and find the view outside dominated by the giant blank stone obelisk of the Washington Monument.

It’s also no coincidence that Trump made his announcement on the day of his trip to Mount Rushmore, which sets the standard for patriotic statuary, attracting 3 million visitors a year to gawk at its enormous bas-relief presidential heads. But whatever you might think of Gutzon Borglum as an artist, or his choice of subjects to honor, the sheer scale of the work exerts its own kind of kitschy fascination; the word “monumental” could have been coined with Mount Rushmore in mind. Trump’s announcement didn’t stipulate the size of the statues he envisions for the Garden of Heroes, but it’s unlikely any of them will be 465 feet tall, the approximate scale at which the Mount Rushmore faces are carved.

Nor, presumably, will any of them speak or move, which is a unique and much-parodied feature of the Hall of Presidents at Walt Disney World, which houses life-size animatronic figures of all of them, from George Washington to Donald Trump. (When the Trump figure was added in 2017, a lot of people thought it looked more like Jon Voight, illustrating the challenge of attempting lifelike three-dimensional representations of actual people.) When Travel and Leisure magazine ranked 56 rides and attractions at the park, the Hall of Presidents came in 48th, with the notation that “it’s not nearly as boring as the reputation that precedes it.”

Of course, the Garden of Heroes won’t be bound by the same necessity to immortalize William Henry Harrison, James Buchanan and Warren Harding, among other third-tier presidents. The executive order designated 30 initial honorees (counting Orville and Wilbur Wright, who are listed together as one).

The list reflects a strenuous effort at political log-rolling, balancing tributes to assorted right-wing heroes — Ronald Reagan, Billy Graham and Gen. Douglas MacArthur — with a fairly anodyne list of progressive icons (Jackie Robinson, Martin Luther King Jr., Harriet Tubman). Some of the choices seem idiosyncratic (Dolley Madison) or pandering (Frederick Douglass, an obvious choice on the merits, but possibly also included to make up for Trump’s notorious gaffe in which he seemed not to realize Douglass died in 1895), or included to make an ideological point.

Was Antonin Scalia, the only Supreme Court justice to make the cut, really a more significant figure than John Marshall, Earl Warren or the first Black justice, Thurgood Marshall, or the first woman, Sandra Day O’Connor? Someone in the White House seems to have picked up, more or less at random, a book about American aviation for inspiration: Besides the Wright brothers, the list includes Amelia Earhart — essentially, a stunt flier who became famous for getting lost — and doomed space shuttle astronaut Christa McAuliffe.

Does the category of “early 19th-century pioneers” require the presence of both Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett (who, it should be noted, has his own dedicated ride at Disney World)? On a list of just 30, was it necessary to include both MacArthur and George Patton, two World War II generals notable for their belligerence? Were they really more important than, say, Dwight Eisenhower, the architect of the Allied victory in Europe whose memorial in Washington has been stalled by controversy for decades?

Figures associated with the Confederacy are conspicuous by their absence, an apparent reversal of Trump’s position since 2017, when his response to the demonstrations in Charlottesville, Va., was to defend “people that went because they felt very strongly about the monument to Robert E. Lee — a great general, whether you like it or not.”

Any American left off the list — say, Mark Twain, Thomas Edison, Emily Dickinson, John F. Kennedy, Georgia O’Keeffe, Jim Thorpe, Ella Fitzgerald, Daniel Webster or Eugene O’Neill — can still qualify under an open-ended clause covering “historically significant Americans … who have contributed positively to America throughout our history,” such as “the Founding Fathers, those who fought for the abolition of slavery or participated in the Underground Railroad, heroes of the United States Armed Forces, recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor or Presidential Medal of Freedom, scientists and inventors, entrepreneurs, civil rights leaders, missionaries and religious leaders, pioneers and explorers, police officers and firefighters killed or injured in the line of duty,” and a dozen or so other categories embracing virtually the entire spectrum of human accomplishment.

“None will have lived perfect lives,” the executive order concedes, “but all will be worth honoring, remembering, and studying.”

Whatever one might think of Scalia’s judicial philosophy, there is no question his life and views are worth studying, even more so than, say, Betsy Ross’s. The order is explicit about the educational value of statues, calling them “silent teachers in solid form of stone and metal.” But silence is exactly what makes statues problematic as a way to understand and convey history.

They are signposts that point in only one direction, to the past, mute in the face of protests, incorporating none of the nuance that actual historians bring to the lives of people like Jefferson and Lincoln. No wonder they inspire so much rage.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: