The Straight Talk and Philosophical Musings of Chris Cornell

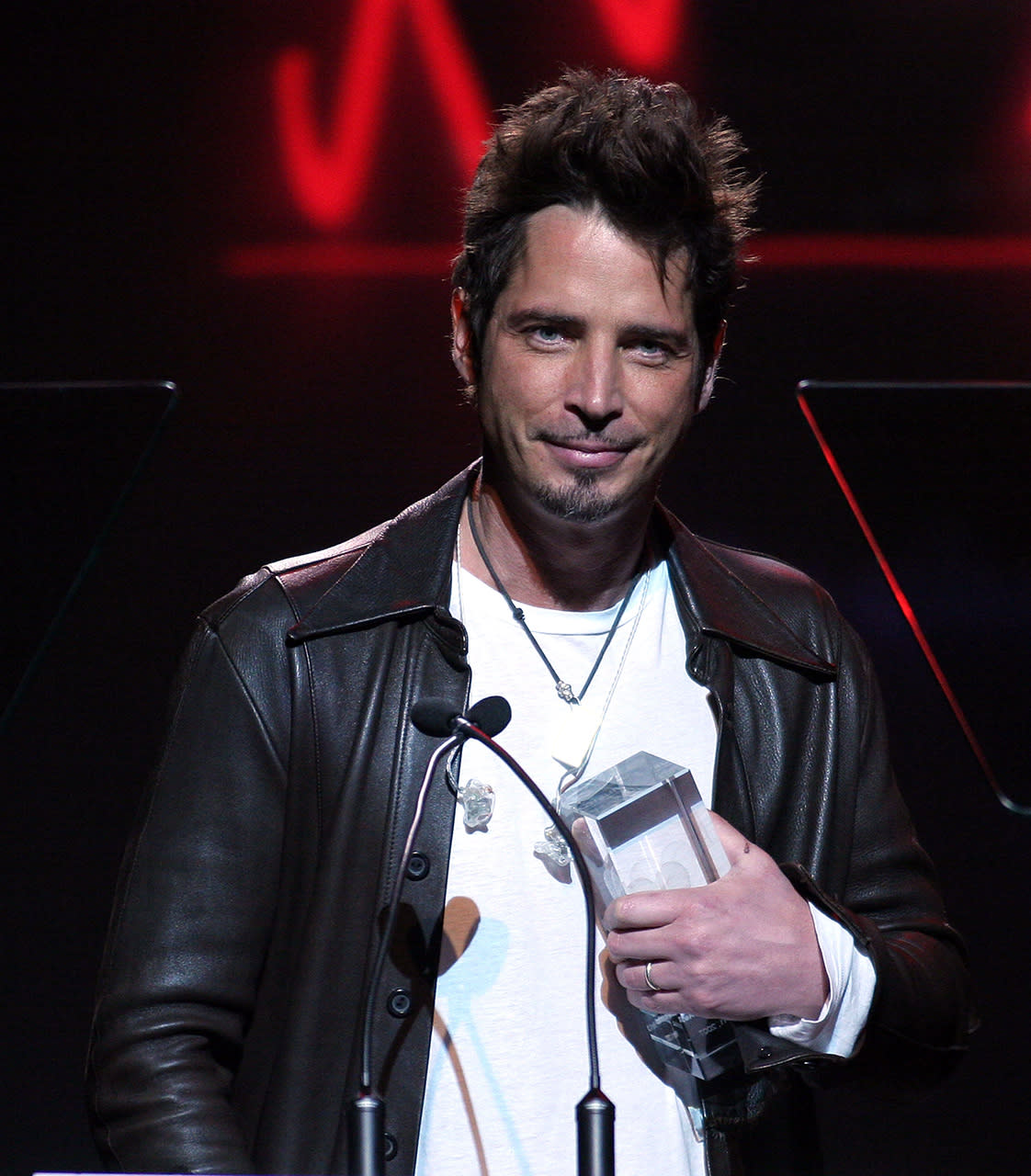

(Photo by Chad Buchanan/Getty Images)

Chris Cornell didn’t like doing interviews, and he didn’t do that many of them. Journalists frequently frustrated him, as he realized that most reporters only wanted to talk about grunge, Seattle, and Soundgarden and had little interest in whatever project he was currently working on, be it a soundtrack score, a solo album, or the charity he launched with his wife in 2012. That organization, the Chris and Vicky Cornell Foundation, was established to provide support for poor, homeless, abused, and neglected children, and it was extremely important to Cornell. He wasn’t an abused child, but he was never close to his parents, which saddled him with trust issues for much of his life.

Related: Remembering the Life and Pondering the Death of Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell

Most of the time, Cornell had every reason not to trust reporters. But when interviewers were straight with him about the topics they wanted to discuss and they knew their history, he respected them, even if he didn’t always tell them what they wanted to hear. Then there were the times Cornell felt engaged and stimulated, and it was then that he could be downright chatty. He never talked frivolously or jumped incoherently between subjects. He thought carefully about what he was saying and was open to being challenged with provocative questions, as long as they weren’t too personal. Cornell guarded his privacy and tended to deflect questions about his personal life. But sometimes he opened up and revealed the sensitive, thoughtful individual that lurked within the soft-spoken, loud-voiced musician.

Related: Chris Cornell Flashback Q&A: ‘We Have to Be Aware That Life Is So Short

The following interview was compiled from two conversations conducted at pivotal times in Cornell’s life. The first took place in 1999, about two years after Soundgarden broke up and Cornell was preparing to release his first solo album, Euphoria Morning. The other interview happened in 2005, shortly before the supergroup he formed in 2001with members of Rage Against the Machine, Audioslave, released their second record, Out of Exile.

Related: Garbage’s Song ‘Fix Me Now’ Was Originally Called ‘Chris Cornell’

During both interviews, Cornell agreed to talk about Soundgarden, the rise and fall of Seattle’s “grunge” movement, songwriting, Audioslave, and parenting. And in the process, he revealed maybe a little more than usual about what motivated him, his attitudes about fame, and his belief that life is simple, yet most people make it into a complex, anxiety-provoking spectacle that prevents them from being balanced. If only Cornell had thought back over some of his own wise advice before he so shockingly took his life this week at age 52.

YAHOO MUSIC: Can you believe how much time has passed since Soundgarden’s first EP Screaming Life [which came out in 1987]?

CHRIS CORNELL: Sometimes it seems like it’s been 30 years, and sometimes it seems like it’s been just a few years. It’s kind of a blur, to a degree. When you’re out on the road touring and touring and then making records, you’re just constantly looking forward, constantly working. You don’t really stop to look at where you are or where you’ve been.

Don’t you ever wish you could sit back and smell the roses?

I suppose if I weren’t doing what I loved, I’d feel that way. But I’ve loved making music since I started and I’m still doing the same thing, only I’m better at it. It’s a lot easier, I have a lot more experience at it, and I’m still having the same kind of success. Part of that is to the credit of Soundgarden, largely because we never painted ourselves into a corner musically. We were constantly changing, constantly growing, and therefore it put us, and also me, into a position where I’m not stuck doing one thing.

You were an important part of a significant era of music history. The Seattle music scene inspired so many people and influenced so many bands. When you look back at film footage from that time, it seemed like everyone was breaking new ground, purging their demons, and having a blast. Do you have any stories about crazy things you did while hanging out with the guys from Pearl Jam, Nirvana, Alice in Chains, and Mudhoney?

It was weird. We were friends with all those musicians, but we were all touring like crazy, so we never saw each other, really. The best time was before there were any bands touring, when we were all just playing clubs and doing what we did. That was fun and there were some good drinking stories — that I won’t tell you. But once different bands had a degree of success, we were all gone. We weren’t here anymore. So, it was very different.

The so-called “grunge” scene was plagued by heavy drug use. Did you experience a period of addiction like many of your peers?

I was always more of a drinker. Seattleites drink beer and rock out. That was sort of the way it was. And then with Soundgarden, we were very unrock. We were not living a Motley Crue lifestyle. But we were a group of eccentric, willful people, so it was pretty crazy.

Why do you think several celebrities from the Seattle music scene suffered premature deaths? Was the stress of being under the microscope too great for them to handle?

I think it’s just natural. It happens in every walk of life. There are a lot more people that die of drug overdoses that worked construction jobs and ended up under a bridge than there are musicians who overdosed and died. I’ve been going to AA meetings, for example. Most of the time, I’m the only musician there. It’s just that when you’re a musician and you’re famous and you have drug problems and blow your head off, everybody knows about it. If you’re somebody’s brother that was always quiet, who seemed to be a nice guy, nobody even knows your name. So I never thought there was some scourge of the Seattle music scene or some sort of a problem with it or something to figure out. It’s just something that’s a part of life. And if you look at the history of rock, particularly successful musicians, there’s not a scene from anywhere that’s not fraught with that kind of stuff — death and disaster.

Some of your lyrics seem to be about the misery, even worthlessness in the face of goodness.

Some of that stems from being in a situation where suddenly you’re on television and on the radio and you’re on magazines — and I’m not just talking about me, but also about what I’ve seen with other people in that situation. An audience is sort of drawn to them as a leader, and the audience is sort of saying, “I’m following you, so where are we going now?” And sometimes I will respond to that by saying, “Just because you know who I am, and in some way I’ve been celebrated, it doesn’t mean I know something that you don’t. It doesn’t mean I’m suddenly invulnerable. It doesn’t mean I don’t have the same day-to-day problems.” And that also has to do with money and music, because there’s so much talked about when an artist becomes successful, about how much money they’ve made. And the funny thing is, musicians don’t make that much money compared to a lot of other people in different professions. You could start your own machine shop and end up making a hell of a lot more money than you can as a musician. And very few musicians are ever even successful. If you wanna make money in music, you’re better off being on the business end of it a lot of the time. And also as a musician, if you do make money, it means you had to bite and scratch and kick the whole way to not get ripped off, because at every corner there’s somebody there waiting to trip you up and take a bigger chunk. That gets frustrating after a while.

When Soundgarden were in their commercial peak, you were looked upon as a spokesperson for a generation of lost, lonely, disaffected, angst-ridden teenagers looking for the path to nirvana. No pun intended.

Yeah, and at the same time I was also focused on by the media as being the frontman for a band where nobody seems to be overdosing or having uncomfortable moments in the media or having their lives seemingly falling apart because of their success. So I would get calls all the time saying, “Yeah, we’re doing a drug issue, and we want your comments because you don’t do drugs.” And it got to be uncomfortable. It was as though people were suggesting that I was the well-adjusted one, which I didn’t feel was true at all. Maybe I dealt with the issues a little differently, and certainly not as openly at all. I mean, I’ve always been very private, and I didn’t feel like I’m the kind of guy that should be going out and saying, “Yeah, you can do this and be level-headed and well-adjusted and it’s no problem,” because I didn’t feel like I was that way through a lot of that period. I just kind of hid behind the curtain and dealt with my issues in my own way. And it wasn’t nearly as visual as a lot of people because I didn’t make myself as available.

Did that put you under a tremendous amount of stress and strain?

With the first period of real success, the thing that kept coming back to me was, “Just stick to who you are and your roots and your friends and family and what you’ve always known while you were writing these songs that people like, and don’t worry about responding to the outside world as a whole.” Because suddenly, if you sell 5 million records and then you sit down and try to consider 5 million people, you’re f***ed because it’s not possible. Most people have a hard enough time dealing with the fact that they have a relationship with 15 people. You can’t have a relationship with 5 million people. And there’s an adjustment period in there. But for me, my responsibility as an artist, whether I’m selling millions of records or I can’t even get a record deal, is I’m just writing music that I’m inspired by, and being who I am and projecting that as much or as little as I want to. And that’s it.

So the process of making music didn’t change with success?

The expectations were greater. But from the moment I started in a band, I would always sit in a room and write songs and I didn’t want that to change. I didn’t want to react musically or verbally in any situation considering millions of people. I had to just consider my life as it has been. And the positive angle to that is when you sit down to write the next record, things really haven’t changed. You’re still writing from the same spot that you were in before. And life does change in those situations and your music can reflect that here and there, but it doesn’t have to be a direct reaction to it. I would notice that throughout history if a band had really big success, they would immediately try to turn the corner and write something that was clearly not for the masses. And I’ve never considered that to be any different than trying to write for the masses because ultimately, if you’re reacting to them, then you’re letting them decide what you’re going to do. Even if it means running away from them, you’re still considering them first and then writing second.

Were there times in Soundgarden that you didn’t enjoy the success you were garnering?

Well, there were moments when things felt uncomfortable to the point of, “Wow, we’re really not where we belong right now.” And the industry and the media kind of push everybody in the same direction and treat everything the same way. I think about the time we were opening for Guns N’ Roses, I suddenly thought, “Wow, all these people, whether it’s the record company or the fans or the people we’ve grown up knowing, have always said, ‘You guys will be the arena rock band of the future.’” And we’d say, “Huh?” And so here we are opening up for Guns N’ Roses on this huge stage in front of thousands and thousands of people, and it just didn’t feel right. I think that was the first moment when I realized that really wasn’t our direction. In spite of the encouragement, that’s not where we belong. And I would think of music we all liked as a band, that we all thought was great, and 99 percent of that music was from bands that never had a gold record, that never saw the inside of an arena unless they were going to a baseball game. So it made sense. It wasn’t a hard feeling to accept.

What led to the end of Soundgarden?

We had done virtually everything that we had wanted to do in terms of how we approached being a band. We had just finished an album where we self-produced it entirely. We had been a band for 13 years, and Soundgarden had become its own entity sort of. It almost created its own legacy away from the guys in the band. And at a point, we felt it would be a really amazing time to just walk away from and go our separate ways and try other things.

Was there a definitive moment where something happened that made you decide to call it quits?

It was just an overall feeling. A lot of it had to do with touring. It’s something that’s sort of necessary, and it’s something everyone was getting a little tired of because we had done so much of it, most of it actually before we were commercially successful. But I think we were all pretty sick of touring at that point and we wanted to have our lives back.

Was there any ambivalence or animosity when you split up?

There’s no animosity at all. It was clear to everyone that unless we’re all 100 percent on board, really wanting to continue, than it might not always be so great. Something might go wrong somewhere. And if someone left the band, for instance, there’s no way we would have continued. I wouldn’t have wanted to because we felt like so much of a family that if anyone hadn’t been there, it wouldn’t have worked.

After leaving Soundgarden, did you know right away that you wanted to record solo albums? Had you considered other options like playing in another band or becoming a producer?

I was going to make a home exercise tape, and I thought, “Hmm, that will actually be hard.” No, I knew I wanted to work on something else musically right away. I thought about starting another band for probably two seconds, but when you’re in a band for 13 years, the last thing you really want to do is start another band. Soundgarden was incredibly democratic, and I was really proud of that. I felt like we got along better than most bands we toured with and most people we knew. And at the same time, when you’re that democratic and concerned with each other’s opinions, you’re always concerned with what the other people think. So what could be more of a left turn from that than being in a situation where every choice is mine and whatever happens is going to be because of me? The other side of it is if it sucks, you’re responsible for that, too. But that’s fair.

After a major lifestyle change, there’s always a period of reconstruction, a time where you wonder what lies ahead and whether you made the right decision. Is that something you faced going into your solo career?

There were moments of that. But there was also this amazing freedom. I would wake up in the morning and I would write a song, and I was really passionate about it. And that was it. I knew right away that it was going to be on the record, and it was gonna be on the record in the form I wanted it to be in. And that’s the ultimate freedom. So it’s kind of a give and take. I loved being in a band and I completely understand why being in a band is different than having a solo career, and I think both are great. But having a solo career is fresh, and of course, having a band is something that I did for a long time.

You don’t seem like the kind of person to leap without first looking. Do you think you ever overthink situations?

I seem to work things out in my head a lot, but I’m not sure how much of it translates into the real world. I could sit at home and think about a particular topic for two months, and have really specific thoughts on every angle and every aspect of that idea. And then someone could ask me about it, and whatever comes out of my mouth might not have anything to do with what I was really thinking about. It’s weird, because I spend a lot of time in remote places wandering around by myself. And then the next thing you know, I’m playing in front of people in a big city, and everyone is focusing on me. That can be a really unsettling, strange thing. But when you’re in a situation of chaos and being unsettled, that’s also really interesting and unpredictable, and if you embrace it, it can be a really magical feeling.

Much of your solo material is softer in tone and delivery than what you did in Soundgarden.

I really wanted to stretch out as a singer-songwriter. I had been in a hard rock band for a lot of years, and listened to a lot of heavy music, and had no interest in doing that specifically as a solo artist. I think, as time goes by, that the more emotional stuff is more exciting to me because it’s real, and there’s a danger to that. Even though in a lot of cases the music will sound less dangerous, it’s more challenging for me, personally. And I think people connect to anything that has a certain amount of vulnerability to it, just like they would connect to a visceral rock anthem where they can stand up and throw their fists in the air.”

The first Audioslave album reflected that kind of vulnerability. There was a real search for healing. Lyrically, it seemed like you were in pretty bad place.

I was in an absolutely miserable state of mind when I wrote the lyrics for the record. I’ve never been beyond hope, so I was looking forward to a way out and feeling better. Mainly I had alcohol abuse issues. Whether it was from a bad marriage or a lot of questionable friendships, a lot of it was coming to a head all at the same time and I didn’t feel good. I had a new band. That felt great. And everything within that was going well, but the rest of my life was falling apart and was a real mess.

How did you cope with that hardship?

I think that pain tends to be something that eventually you can’t take anymore, and that can be the thing that’s eye-opening. That’s what happened to me. I was in a horrible situation with something that was not my fault — a relationship that was destructive and was not my fault. And at some point, I was in too much pain to deal with it. And being somebody that always drank, suddenly for the first time in my life I was really f***ing overdoing it. And at a time when I felt I should be through with anything like that, I was suddenly someone who had a serious alcohol problem, which made everything 10 times worse. There was 10 times more pain, 10 times more depression, more confusion, and even less of an ability to see where it’s coming from and do anything about it. And then that was spilling into other areas of my life.

Was that the point when you realized you had to cut off ties with your ex-wife?

It was a lot of things. I had to do a lot of things that were very difficult. And after doing all those difficult things they bore fruit, which you can see on the second [Audioslave] record. I found myself in a new incredible relationship, which has changed me personally in every way at a time when that was something I wasn’t really looking for. It wasn’t an easy period. It was horrible. Horrible. But having to eventually butt heads with it and make decisions which were very difficult to make was valuable. I essentially left my entire past behind and pretty much everyone that I knew from Seattle and everything that was negative, and just moved on. A lot of people have trouble doing that and they just never get over it. And it is a difficult thing to do.

When you leave everything you know behind, you have to start anew, which is always hard and sometimes debilitating.

That’s why I went to rehab. I ended my marriage. I started going on tour and I met my current wife, which was a huge life change. I was already trying to dig myself out, and then that relationship challenged me on every level that way — and all in positive ways. I was in such a different place when I was writing lyrics for the record, being remarried, I’m in an amazing relationship. My wife Vicky was actually six or seven months pregnant when I was writing the bulk of the lyrics for that album, and that stuff came out.

How did becoming a father again affect your disposition?

Oh, man. I’m with my 7-month-old all day and all night and I’m happier than ever. When you become a parent, you leave a lot of things behind and refocus, maybe on how simple life really is and what few things there really are to worry about. And everything else can go by the wayside. A lot of the things that concern us in daily life are frivolous and silly compared to how much a child needs you and how simple their life is. And that also is a big deal. Like, there are so many people who don’t have children who are on spiritual quests and are trying to live in the moment. I don’t know how many times over the past 10 to 15 years that I’ve heard about living in the moment, living in the moment. And I’ve lived a lot of my life not really knowing what the f*** that’s supposed to mean. But having a baby kind of pointed that out to me. When I’m with her I’m not thinking about anything else. It’s just a huge, positive thing. And you know, one of the great things about it is if you don’t ever have kids, maybe you don’t know what you’re missing so maybe it’s OK. And if you do, you see people who don’t or never have or never will and it’s like, OK. But they’re kind of missing out on something. Not that everyone should have kids. Because a lot of people shouldn’t and there are a lot who I wish didn’t, but it’s weird. It’s just such a huge, mind-broadening event.

Do you have any advice for new, frazzled parents?

It’s all about co-existence. Children, I think, should become the friends of their parents. That’s what I missed out on in a lot of ways with my upbringing. There was the person that maybe was in charge of making my childhood a secure one, and making sure there was a roof over my head and food on the table — someone to provide discipline or direction in whatever way they thought was right. But being friends with my parents never happened. And when that’s not happening, then there’s not trust. And for me, with children, they’re my best friends. Right now, my wife and my daughter are my best friends. And that changes a lot of things, too. You’re not gonna see me hanging out with a bunch of dudes drinking beer or see my at the club or whatever. And I feel like in a lot of ways, I know people think that they’re gonna miss stuff like that, but God, I don’t miss hanging out with a bunch of dudes and getting drunk at all. My life is so much more fulfilling and I realize how valuable time is now, as you know when you see the difference a week makes in a toddler’s life. Being on the road, sometimes I won’t see my baby for a week, and Jesus Christ, that’s valuable time lost. I get home and a week has gone by and she looks different and does something she didn’t do before. For me, that really points out how valuable it is to be there with your children.

How was being in Audioslave different than being in Soundgarden?

That question can’t really be answered. It’s two completely different worlds and I’m in a completely different time in my life. There are a lot of similarities, but also, I’m in a band with three other guys who are older than anyone in Soundgarden was when I was in that band. So it’s hard to say.

Your lyrics have always had a spiritual quality.

I’m not sure about the word “spiritual.” “Philosophical” might fit more. And it’s not something I’ve concentrated that much on. I’ve always had an attitude towards people that are always getting new books and trying to discover new types of what they refer to as spirituality, which is totally what I would imagine distracting them or me or anyone from what is really going on, which is that we’re here now doing stuff. And whatever happens later, great. And if you don’t feel good, probably changing your behavior one way or another is all you need to do. It can be that simple. If you’re good to people, people will be good to you and things will be good, and if you’re not then they won’t and people won’t. Again, it’s something very simple. I’ve read a lot of books about the origins of a lot of different religions and the history of them and the things they’ve done, and most of it, when we’re talking religion, is not good. Some of it is a lot of well-meaning people, but then numbers create power and then power becomes corrupt and then bad things happen.

Describe the philosophy of Chris Cornell?

I agree with the philosophy of J. Krishnamurti. It’s up to the individual to make their own decisions about spirituality and what they’re really searching for. The spiritual path isn’t a path; it’s pathless. And he would say that to sit around in the ashram and meditate is a waste of time, and yet this guy was considered to be an incredible spiritual teacher. He just called bulls*** on it, mostly. He said that to even have a spiritual leader is bulls***. And to me that attitude is very refreshing. It makes a lot of sense. I think a person knows in their gut if something’s good or if something’s not good and that’s all you need. You just have to learn when to call bulls***.