How only luck and timing kept me from being a child asylum seeker tear-gassed at the border

This is a personal essay, and the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of Yahoo Lifestyle.

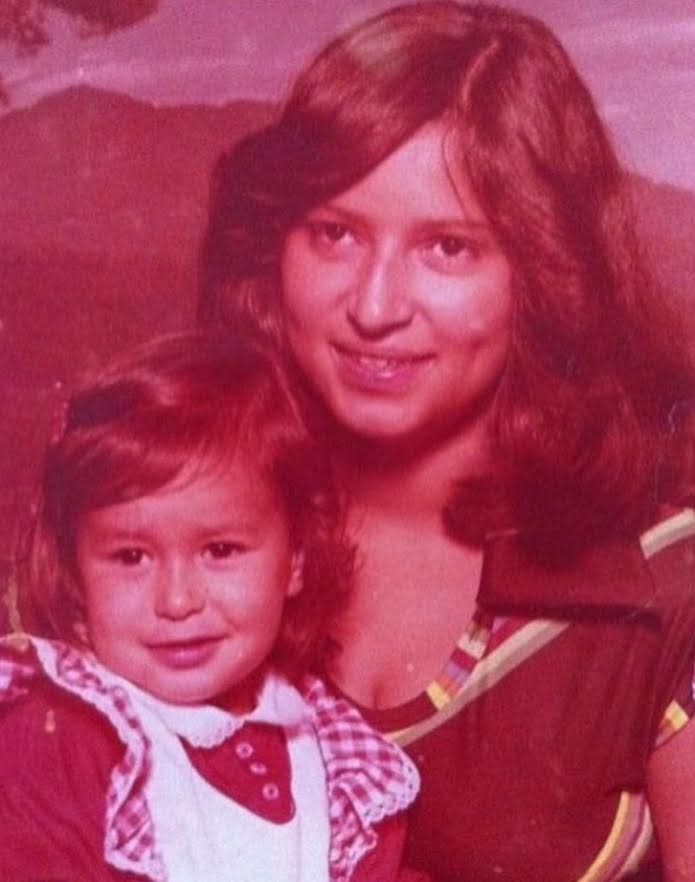

As I watched the shocking footage of unarmed asylum seekers in Mexico fleeing for cover as the U.S. government unleashed tear gas and rubber bullets this week, I felt as if someone had reached into my chest and squeezed my heart. That could be me, I thought. I felt weighed down by my privilege as a 36-year-old New York professional, replaying in my mind, over and over, the story of my mother — Cilia de Jesus Bustillo, who fled Honduras back in 1975 as a frightened teen, my sister secretly in tow.

Five years before her journey, when Cilia was just 12 years old, her mother, Beatrice, left her behind in Honduras after convincing the local consulate to give her a U.S. tourist visa. My grandmother settled in Morristown, N.J., where a diaspora of Central and South American immigrants had formed, creating their own colorful community. She outstayed the visa and began working at a local factory, and soon met and married Manuel Oliveras, which allowed her to become a U.S. citizen, entitled to request residency for her minor children: my mother and uncles Xavier and Hugo.

But it would take five years for that paperwork to be processed. In the meantime, my mother was orphaned. She struggled to survive poverty and the wrath of her brother, Jamie, who molested and abused her. In one incident, Cilia asked him for permission to go to a summer carnival with friends, but he forbade it. Desperate to escape, she snuck out of the house, believing she had done so undetected. But she returned home to find him waiting outside on the porch, standing with a bucket of scalding hot water at his feet, swinging a thick leather belt. She begged for mercy.

“Pero no hice nada!” “I didn’t do anything!” she cried out, as he beat her with the drenched leather strap. The blasts from each lashing rang loudly in the night, like firecrackers. “La vas a matar!” “You’re going to kill her!” an alarmed neighbor shrieked, running to her house and returning with a machete. “Deja esa nina o te corto en pedasos!” “Let go of that little girl or I will cut you into pieces!” she told my uncle. So he did. He dropped my mother’s body, inches from death, and walked away.

After that night, at 13, Cilia became hardened and ornery. The neighbor nursed her back to health but couldn’t have her stay for long. Abandoned and without protection in a lawless country — where a postwar civil unrest would soon lead to military rule — she had nothing but her mother’s promise that she’d soon join her in the United States. She kept to the streets, finding generosity in the local grocer, Ana Luz, who gave her food and small jobs. But she longed for her mother. When hope failed her, she’d look to her grandmother — who, unbeknownst to her, pilfered the money and gifts Beatrice sent, keeping the letters and photos that my mother needed most.

Years passed without change until she fell prey to a young man named Jamie, the son of wealthy cow farmers whose family controlled the town. Although she was shy and defensive, having endured countless acts of sexual violence by age 16, he convinced Cilia, who lived a life without love or affection, to go on a date.

Jamie spoke to her sweetly and told exciting stories of his visits to los Estados Unidos. He bought her a Coca-Cola, her favorite, which he laced with some of the tranquilizers that he had access to from his family farm. She regained consciousness in the back of his red Mustang as he raped her. She cried out for help and he apologized, saying he didn’t know she was a virgin. He’d heard on the streets that she was a puta, a “whore.”

Weeks later, my mother learned she was pregnant and was kicked out of her grandmother’s home. When her rapists’ family learned of her condition, they kidnapped her. They held my mother on their farm, hours away from home, and promised her safety in exchange for a contract to turn the baby over at birth. My mother agreed to sign in the morning. But once everyone had gone to bed, she stole as much money as she could find and escaped. Back on the streets of La Ceiba alone, now six months pregnant, she feared retaliation.

My mother was hopeless and prepared to cross the border by any means when her admission to the United States miraculously came through. A path to salvation seemed sure, until her brother heard that all incoming visitors had to pass a health examination. No pregnant minors would be allowed entry. But my uncle, Hugo, recruited a girl in town to impersonate my mother, giving a blood sample, and they were cleared. A local seamstress fashioned a dress that would hide her growing belly, and they were off. For the entire five-hour flight, she never moved from her seat. She barely breathed.

Cilia arrived in this country on April 4, 1975. My sister Karina was born in June at Morristown Memorial Hospital, an American citizen. “No matter what,” she thought, “my daughter is safe.” Five years later, she had a second daughter, Karla, with my father Carlos, an immigrant from Ecuador. They married in 1981 just before my birth, in November of 1982, in San Antonio, Texas.

I was raised in a humble home peppered by the consistent foot traffic of migrants whom my parents were eager to help. Through their commitment to the Latinx community, I learned that abundance is multiplied by generosity. I understood the meaning of humility and witnessed the rapid progress of so many hard-working families who have become an integral part of the American fabric.

In today’s political climate, families like mine could cease to exist. The essence of what it means to be Latin American, our collective history of migration, is being criminalized, used by fellow Americans to label and shame, and manipulated by our current administration to violate international treaties protecting human rights.

As a first-generation Honduran-American woman, I see myself in these migrants. Only luck and timing separated me from being one of those mothers or one of those children. This week, with the arrival of asylum seekers surging, the United States shut down its border crossing. The Department of Justice and Department of Homeland Security recently announced a new 78-page rule amending the process, barring some from eligibility completely, and effectively turning racism into policy.

Immigration and the absorption of refugees are complex issues, but at the heart of these dilemmas are human lives. And humanity should never be politicized.

When I ask my mother now to name the driving force in her survival, she says, “You never give up on your child.” I don’t know one person who cannot relate to that.

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

This man was granted U.S. asylum for fleeing anti-gay persecution in Nigeria

LGBT asylum seekers first migrant caravan group to arrive at U.S. border

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.