New 'Black & Blues' documentary reveals a defiant, angry Louis Armstrong the world didn't see

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Mention the name Louis Armstrong, and certain sounds and images of the 20th-century jazz genius flood in.

Screaming trumpet high notes. That gravelly "Hello, Dolly!" croon. Bright eyes and a toothy grin.

But director Sacha Jenkins wanted to go beyond that caricature to shed light on the deeply proud, cunning, funny and pained man behind the myth. He’s done that with "Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues" (streaming Friday on Apple TV+), which is anchored by a treasure trove of previously unreleased conversations recorded by Armstrong.

The documentary – which coincidentally arrives the same day as a new Armstrong holiday album, "Louis Wishes You a Cool Yule" – focuses intently on how Armstrong, commonly called Satchmo or Pops, stayed true to himself while navigating incessant racism. During the civil rights movement and beyond, many Black Americans viewed Armstrong as a subservient Uncle Tom figure, a perception "Black & Blues" refutes.

We tour the doc’s more poignant revelations guided by Jenkins, whose previous films have explored the cultural impact of Rick James and Wu-Tang Clan:

From Lizzo to Selena Gomez: 19 new music documentaries ready to rock your world

Louis Armstrong’s fury and indignance are clear in home audio tapes

For decades, Armstrong recorded conversations with his wife and friends on reel-to-reel tape decks both on the road and at his New York home, his habit for documenting his life. Jenkins employs them freely in his documentary, and Armstrong's anger and coarse language paint a different picture of the entertainer.

"In one tape, we hear him say, 'When the (expletive) have I Tom'd?' and that made me have to think, when did he, really?" says Jenkins, who notes that while he was growing up in the militant hip-hop '80s, he viewed Armstrong as a smiling sellout.

The documentary features Armstrong recounting many painful instances, including once when a white emcee refused to introduce the musician after referring to him with a racial slur (Armstrong introduced himself to wild applause), and another when a white fan told Armstrong he had all his records, even though he did not like Black people. "His ability to keep cool in the face of all this was astounding," says Jenkins.

COVID is robbing musicians of their final chapter: And fans of their swan song performances

He fought racism with personal advancements

Born in 1901 in New Orleans, Armstrong was "a hop, skip and a jump away from slavery," says Jenkins. "He had to do all kinds of things to survive."

Through much of his career, the trumpet player often could not even sit in a club where he was the featured performer. But as his fame grew internationally, he began to put his foot down.

"For much of his career, he had to think about how he was going to feed himself, but as his stature grew, he began to say, 'Unless I can stay here, I’m not going to play here,’'" says Jenkins. "So while he didn’t say he was a civil rights activist, he was one in moments like that."

New movies this weekend: Watch 'Tár,' stream 'Wendell & Wild,' skip 'The Good Nurse'

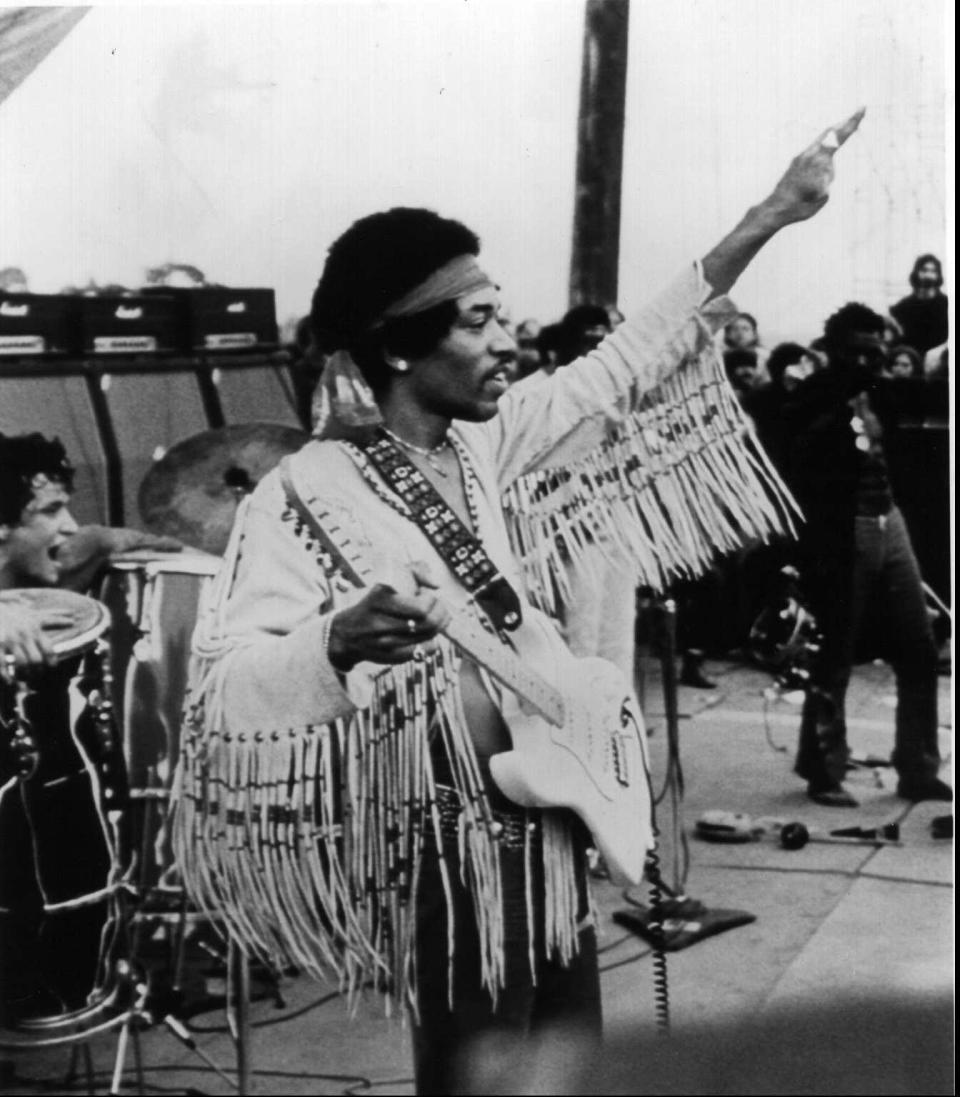

Louis Armstrong re-imagined 'The Star Spangled Banner' long before Jimi Hendrix did

Early in his career, Armstrong added the national anthem to his repertoire. It was a choice filled with conflicted feelings that speak directly to the Black American experience, says Jenkins.

"There’s a duality for Black folks when it comes to patriotism, so the way you play that song is about the temperature in the country and about how Black people feel about being American," he says. "On the one hand, Armstrong says playing it made him 'feel like somebody.' On the other, there’s always that element of loving the country but dealing with a country that doesn’t love you back."

While the Hendrix version unveiling at Woodstock caused an uproar, with its screaming bomb sounds at the height of the Vietnam War, Armstrong’s version was more nuanced. "He used that song as a vessel," Jenkins says.

Ready to buy a VIP concert package? Here's how to avoid getting ripped off

The musician’s career was guided by mobsters

Among the many obstacles Armstrong dealt with in his career, from racism to sore lips, a persistent thorn were the white club managers who felt they could order around their performers, says Jenkins.

Armstrong dealt with a number of club-owning gangsters early in his career, once even being commanded to perform in New York at gunpoint. Eventually, he found Joe Glaser, a manager whose Mob connections helped smooth out some issues – but at an emotional price.

Jenkins recounts how Armstrong once went on a national talk show and explained calmly to the host how he had been advised to find a powerful white ally who would consider the Black musician his property.

Says Jenkins: "Well, at the height of Black consciousness, the only reaction to that is, 'What are you doing, old man, you’re hurting the cause!' But the question really is, given his times, was he not just telling the truth about the way it was?"

You won't recognize it: John Lennon originally sang 'Yellow Submarine' as a sad song

For a 20th-century superstar, Louis Armstrong led a humble life

Armstrong was a pioneer: He was celebrated internationally on nearly every continent, even making a trip to Ghana where local trumpet players greeted him at the airport. He also starred with top billing in many Hollywood films at a time when Blacks actors couldn’t get roles.

Yet he lived the last decades of his life (Armstrong died in 1971 at age 69 of heart and liver disease) in a modest home in a working-class area in Corona, a section of New York’s Queens borough.

Jenkins thinks there's a lesson for today in that humility.

"He didn’t want to live a super-bougie fancy life," he says. "You think about hip-hop today, artists go around telling you they’re geniuses and how much money they have, how important they are. This guy didn’t have to tell anyone he was a genius or how much money he had. So his story is super-contemporary. People should really study him now, and understand we can do better."

Far from 'a great big hug': A new 'Barney' doc explores love, hatred and tragedies

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Louis Armstrong 'Black & Blues' documentary rejects sellout image